Subscribe to Our Newsletter

A Tale of Two Painters

They never met in life, but Willem de Kooning and Chaïm Soutine have an artistic kinship that transcends time and place.

By John Dorfman

Chaïm Soutine, Landscape with House and Tree, circa 1920–21, oil on canvas, 55 x 73 cm.

The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, Artwork © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS). New York Image © 2021 The Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia

In 1977, when asked to discuss his influences, Willem de Kooning pointed to one above all—Chaïm Soutine, the Russian-born Parisian painter who died in miserable circumstances in 1943. In some ways, it seems like an unlikely affiliation. The two artists came from different backgrounds, worked in different periods (despite being only a decade apart in age), and had no personal contact with each other. Furthermore, Soutine was a figurative painter, while de Kooning was a member of the Abstract Expressionist group. So why did de Kooning place so much importance on his encounter with Soutine? And what exactly was the nature of that encounter?

Answers to these questions are being offered by an exhibition at the Barnes Museum in Philadelphia, an institution that is intimately linked with Soutine’s reputation in the United States and has long been known for innovative and unconventional approaches to art and art history. “Soutine / de Kooning: Conversations in Paint,” on view through August 8, is co-organized with the Musées d’Orsay et de l’Orangerie in Paris and presents 45 paintings by the two artists, including many Soutines that were purchased by Dr. Albert C. Barnes, the museum’s founder. The curators place the paintings in dialogue with each other—a conversation the artists themselves were never able to have in life—revealing deep resonances.

Willem de Kooning, Queen of Hearts, 1943–46, oil and charcoal on fiberboard, 117 x 70 cm.

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1966, Artwork © 2021 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Image by Lee Stalsworth, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

It is noteworthy that de Kooning and Soutine belonged to different artistic generations, even though they were from the same physical generation—Soutine having been born in 1893 and de Kooning in 1904. That is because de Kooning did not achieve recognition or even come into his own as an artist until the late 1940s, whereas Soutine was an early bloomer and found fame in the late ’teens and early ’20s. While de Kooning was European-born, his career was located entirely in the U.S.; Soutine’s was wholly in France. In terms of personal traits, there were similarities: Unlike many modernist artists, Soutine and de Kooning were exceptionally oriented to art history and saw themselves as being in a continuum with the great art of the European past rather than in rebellion against it; both were obsessed with Rembrandt in particular. Both got more education from going to museums and galleries than from formal study. Both were marginalized immigrants—Soutine a poor Jew from Russia living in Paris, de Kooning a Dutchman who stowed away on a ship to get to New York. De Kooning had an admiration or even a feeling of kinship with Soutine’s square-peg nature, his inability to conform to expectations, even those of Paris’ artistic bohemia. Soutine, who died of disease—probably tuberculosis—while hiding out from the Nazis in wartime France, always had a “cursed” aura about him, somewhat like that of van Gogh, that contributed to a certain romantic appeal that de Kooning undoubtedly felt.

Willem de Kooning, . . . Whose Name Was Writ in Water, 1975, oil on canvas, 193 x 222.9 cm.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Artwork © 2021 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

De Kooning’s feeling of connection to the art of his predecessors contributed to his willingness to be influenced by Soutine.“I am one of the artists who likes to be influenced,” he said to the critic Harold Rosenberg. “It gives me another way of looking at it. I find things that give me a kick, that I am attracted to. If I am attracted, it means there is something in it for me.” His good friend Edwin Denby, the dance critic, recalled that for de Kooning, being an artist “didn’t mean being one of the boys, making a scene or leading a movement, it meant meeting full-force the professional standard set by the great Western painters old and new.”

During the 1920s and ’30s, when de Kooning was a young artist trying to make his way in New York, Soutine’s work was being shown in the city; in fact, there was something of a “Soutine boom” going on at the time. The first American to show any interest in the artist was, in fact, none other than Dr. Barnes, who in 1922 bought 60 paintings in one transaction with Léopold Zborowski, Soutine’s dealer, during one his his frequent buying trips in Paris. Barnes showed Soutine’s work at his private museum in 1923, and this exhibition essentially launched his work in this country. In addition to gallery visits, during the 1930s de Kooning was made aware of Soutine’s importance by a friend, John D. Graham, a Russian expatriate painter and art critic who was a key source of intelligence for young American artists about what was going on in the so-called School of Paris. Graham, a somewhat eccentric theorist, in a 1937 article titled “Primitive Art and Picasso,” placed Soutine in the “Perso-Indian-Chinese” lineage of modern art—as opposed to the “Greco-African” (Graham was also a savvy picker of African tribal art, which was avidly collected by many modern artists including Picasso). Fellow Perso-Indian-Chinese included Renoir, van Gogh, Kandinsky, and Chagall.

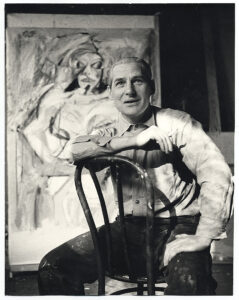

Willem de Kooning with a state of Woman I, circa 1952.

Photo Courtesy Klüver/Martin Archive; Photographer: Kay Bell Reynal. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Artwork © 2021 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In 1943, the year of Soutine’s death, an exhibition of his work, organized by Dr. Barnes, was mounted at the New York branch of the Parisian gallery of Étienne Bignou; the very same gallery, several months earlier, had displayed works by de Kooning alongside those of European artists including Matisse, Picasso, Modigliani, and Soutine—presumptive evidence that even this early someone had noticed something in de Kooning that made it appropriate to place him in proximity to Soutine. In 1950, the Museum of Modern Art mounted a major Soutine retrospective, which de Kooning may or may not have seen. Either way, MoMA curator Monroe Wheeler, in his essay for the catalogue, made a connection between Soutine’s expressionistic, painterly style and the phenomenon of abstraction, posing the question, “Was Soutine…what could be called an abstract expressionist?” Two years later, at a time when he was creating his Woman paintings, de Kooning definitely saw a Soutine exhibition—at the Barnes Museum, of all places. Looking at Woman II (1952) and then at Soutine’s The Communicant (circa 1924) and Woman in Pink (circa 1924), one cannot help but see the similarities.

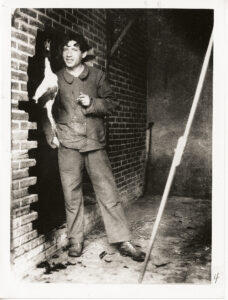

Chaïm Soutine with a chicken hanging in front of a broken brick wall, Le Blanc, France, 1927

Photo Courtesy Klüver/Martin Archive; Photographer: Kay Bell Reynal. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Artwork © 2021 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Wheeler’s question of 1950, as Musée d’Orsay chief curator Claire Bernardi notes in her catalogue essay for “Soutine / De Kooning,” grew out of a tendency at the time for American critics to try and fine antecedents for the newly emerged Ab-Ex movement. Soutine, a devoted painter of the human figure and the landscape (as well as, famously, raw meat), had no patience for abstraction and did not even accept the label of “expressionist.” Nonetheless, there are aspects of his painting that tend toward abstraction, just as de Kooning’s version of Abstract Expressionism always contained figuration. Soutine’s paint handling, always emotionally intense and heavily impastoed, at times gets so wild that the structure breaks down, suggesting abstraction. His Hill at Céret (1921) is a representative example; the landscape dissolves into coiled, oozing brushstrokes. Soutine’s tendency to distortion of the figure, driven by an eye for the grotesque that was shared by others of his generation, such as Picasso, not to mention de Kooning himself, also tends to induce a feeling that some kind of abstraction is going on. A critic of a later and less doctrinaire generation, Arthur Danto, rather than trying to make Soutine into an abstractionist, wrote, “What de Kooning might have seen in Soutine was how it was possible to paint like a New York artist—with gestural slabs and strokes of thick paint—and do the figure: to be abstract and referential at once.”

Chaïm Soutine, Woman in Pink, circa 1924, oil on canvas, 73 x 54.3 cm.

Saint Louis Art Museum. Given by Sam J. Levin and Audrey L. Levin, 1992, Artwork © 2021 Artists Rights Society (ARS). New York, Image © Bridgeman Images

De Kooning spoke of a quality of “fleshiness” that he perceived in Soutine’s painting. The very thickness and sensual quality of Soutine’s paint application could be thought of as fleshy, and the same is often true of de Kooning’s. On the other hand, de Kooning often chose to express fleshiness through the liberal use of shades of pink, flesh tones that could either be depictions of a woman’s skin or elements of color abstraction. For Soutine, flesh as a subject had another side—not the sensual surfaces of the female body but the gory, grotesque, and broken flesh of his beef-carcass paintings. De Kooning never emulated these directly, although the curators of the current Barnes exhibition draw a connection between Soutine’s Side of Beef With a Calf’s Head (circa 1925) and de Kooning’s abstract Whose Name Was Writ in Water (1975) in terms of the way the brushstrokes spread across the canvas. But Soutine’s brutal depictions of this raw subject matter resonated with de Kooning’s enthusiasm for the grotesque, which he absorbed from Rembrandt (from whom Soutine had actually gotten the inspiration to paint the sides of beef) and from his own fellow-countryman Hieronymus Bosch.

During the 1970s, de Kooning moved away from the intense, sometimes grotesque styles toward a lyrical approach in which figuration and abstraction coalesce without tension. Working on the East End of Long Island, a watery place that reminded him of his native Holland, the artist painted abstracted landscapes in bright, airy colors. Sometimes these canvases portray a human figure interpenetrating with the landscape, becoming almost indistinguishable from it, dissolving into it. These late works are full of light, and their luminousness could be considered a sort of afterglow from Soutine’s painting. Speaking of the 1952 exhibition, de Kooning recalled, “I remember when I first saw the Soutines in the Barnes Collection. In one room there were two long walls, one all Matisse and the other all Soutine—the larger paintings. With such bright and vivid colors, the Matisses had a light of their own, but the Soutines had a glow that came from within the paintings—it was another kind of light.”