Subscribe to Our Newsletter

All Too Real

Z. Vanessa Helder, Pettit Carriage House, 1942, watercolor on paper, 15 3⁄8 x 20 1⁄4 in.; Collection of John and Patti O’Keefe

Magic realism, a relatively neglected school of American painting, probed the disquieting truths beneath the surface of modern life.

By John Dorfman

“For Modernism, we may take it that abstraction is the law and that realism is the criminal,” wrote the art historian Linda Nochlin in the early 1970s. At that time, abstraction had already lost some of its dominance, but the point was and still is sound. With the rise of Pop, representation had begun its return to the art world, but of the multiple modes of representational art that have come into being since then, few can be considered “realism.” And with the widespread use of photography and other machine-generated imagery in mixed media, it has become possible, even easy, to engage in figurative or representational art without using the traditional techniques of realist painting at all. So in that sense, realist painters remain outsiders even if they are no longer outlaws. In the mid-20th century, when abstraction was at its high tide in America, to be a realist was a brave and existential choice, and the artists who took that path are, to this day, relatively obscure and left out of the grand evolutionary narrative of modern art.

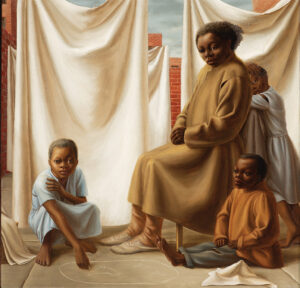

George Tooker, Laundress, 1952, oil on Masonite, 23 1⁄2 x 24 in.

The Schoen Collection: Magic Realism

One particular group of these artistic criminals is currently getting renewed attention in an important and ambitious exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art at the University of Georgia.“Extra Ordinary: Magic, Mystery and Imagination in American Realism,” on view through June 13, brings together a selection of works by mostly less-known artists, spanning the mid-1930s through the mid-1950s, making the case that a special way of seeing and depicting the modern world took hold in this country during those decades. Even if it never became a dominant mode, it was persuasive and pervasive enough to constitute a school, albeit one with no formal affiliations and often no direct connection between the artists. Some knew each other well and even worked together, while others lived in different parts of the country and worked utterly independently. In short, what the curators of the Georgia exhibition call “magic realism” was not a cenacle but a zeitgeist, albeit of a somewhat subterranean type. And as the subtitle of the show indicates, this artistic phenomenon raises some important questions about realism itself. If we are in the realm of mystery and imagination—one that was first charted in this country by Edgar Allan Poe—how can this be realism? The answer is that one’s definition of realism depends on one’s definition of reality itself.

The paintings and drawings on view in “Extra Ordinary,” disparate though they may be, share certain characteristics—precise technique with sharp rendering, an eerie or lonely quality, a sense of silence or even airlessness, and a greater or lesser degree of grotesqueness. The works have affinities with other 20th-century movements in the U.S. and Europe, such as New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) Precisionism, Surrealism, and the American Scene. The comparison with Surrealism is perhaps the closest and most tempting, although most of the artists did not see themselves as being Surrealists. While some of the paintings in the exhibition could be interpreted as depicting dreams, magical realism achieves its magical effects without resort to the oneiric symbolism and distortions of Surrealism. Rather than Dalí, it is de Chirico, with his eerie, empty piazzas, who seems like the progenitor of these artists. The world in their works is basically the real world, seen with eyes shaped by the anxiety, alienation, disquiet, and bewilderment of modern existence.

“Extra Ordinary” takes as its point of departure an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in 1943, “American Realists and Magic Realists.” Curated by Alfred Barr, Dorothy Miller, and Lincoln Kirstein and pulled together in haste at the height of World War II, it drew attention to a type of art that even then was being condemned by critics such as Clement Greenberg, who in his influential 1939 essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch had placed all contemporary realism in the latter category. Greenberg also accused MoMA of “eclecticism” for its willingness to admit figurative art, even of a non-realistic kind, to the ranks of modern art and for mounting exhibitions such as this one and the earlier “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” (1936). The 1943 show is credited with coining the term “magic realism,” at least as it pertains to visual art (rather than the Latin American literary movement), and the magic in the paintings is of a decidedly non-traditional variety—less a matter of lore and legend than an ability to see beneath the surfaces of things, to draw attention to the weirdness of ordinary life.

Peter Blume, Study for South of Scranton, 1930, oil on canvas, 28 x 20 in.

Vero Beach Museum of Art, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Athena Society, 2017.2 © 2020 The Educational Alliance, Inc. / Estate of Peter Blume / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

For some of the artists in the 1943 and 2021 exhibitions alike, what lay beneath was a forbidden sexuality. Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and George Tooker, who were friends, lovers, and collaborators with each other, shared a fascination with Italian Renaissance aesthetics and the archaic, demanding egg tempera technique, and the curators of the Georgia exhibition suggest that their abiding love of realist traditions had a great deal to do with their homosexuality. While straight artists could abandon representation for the disembodied realm of abstraction, gay artists felt the need to hold on to the body and its sensual possibilities in art, because full and honest expression of their desires and identity was denied them in life.

Cadmus’ The Playground (1948), a startlingly frank and feral portrayal of sexuality—both gay and straight—in a public place, sets the tone for this hiding-in-plain-sight school. French’s Music (1943), while it engages in a heightened depiction of the male body, has a symbolic, otherworldly quality that marks the artist’s “interest in man’s inner reality.” As for Tooker, he specialized in using imagery drawn from everyday life to convey the anomie of modern existence. In Laundress (1952), he blends social realism with magic realism—although it should be noted that he disliked the latter term and resisted inclusion in the category—in portraying a Black woman and three children on the roof of a New York building. The laundry hanging to dry behind them forms a screen or backdrop that suggests Renaissance drapery as well as the 19th-century American artist Raphaelle Peale’s Venus Rising from the Sea—A Deception (circa 1822), a mischievous work in which the titular character does not appear because she is almost entirely hidden by a hanging white cloth. The timelessness and even serenity of Laundress points to Tooker’s concern with human universals that transcend time and place.

Many of the magic realist works concentrate on the American townscape, and in these one can see debts both to Charles Sheeler and to Giorgio de Chirico. George Ault’s Black Night: Russell’s Corners (1943) delivers a Precisionist-worthy view of a red barn and a white stable at a bend in a rural road, a scene from the town of Woodstock, N.Y., where he lived, that he returned to several times in his work. Typically for the artist, it is shown at night, with the darkness held at bay by the light cast by a single street lamp. These modernist nocturnes were a speciality of Ault’s and the eruption of light into darkness creates an eerie effect. Ault was plagued by family tragedy and mental illness, and his brand of magic realism portrays anxiety and depression not internally but externally, by showing the world as seen through saddened, troubled eyes.

The little-known Z. Vanessa Helder also used a Precisionist style to achieve uncanny effects. Her watercolor Pettit Carriage House (1942) is both this-worldly and otherworldly by virtue of its extreme crispness of detail, colors that are both muted and slightly garish, and total absence of people. Although she was based on the West Coast, in Spokane, Wash., and Los Angeles, her Carriage House could easily serve as an illustration for an H.P. Lovecraft story of horror in rural New England. Thomas Fransioli’s Rain in Charleston (1951) depicts a real street in the historic South Carolina city, with identifiable buildings, but the way he depicts it qualifies it for inclusion in the category of magic realism. Here the magic lies in the storm clouds and the reflections off the rain-slicked street, and in the near-total lack of human presence. Again, there is the sense of the macabre without there being anything specifically macabre being shown, as if something were about to happen. In O. Louis Guglielmi’s Tenements (1939), the cityscape is a locus of horror in a more explicit way. Again, the scene is unpeopled, and the street in front of the buildings is strewn with coffins, which appear to be made of bricks as well. The implication, fortified by the funeral wreath that surrounds one of the buildings, is that the tenements themselves are coffins; Guglielmi, who grew up in such a place, ought to know. Stuart Davis admired Guglielmi, who he said “produced many paintings within the framework of familiar images that have the unfamiliarity of life.” Despite the apparent grimness of many of his paintings, Guglielmi said, “My attitude towards painting today is to be clear, to be saturated with hope, to give the people a reason to live out the débris of our years.”

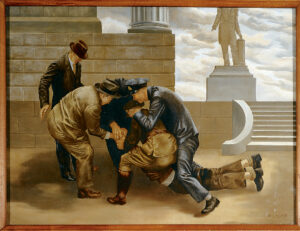

Henry Billings, The Arrest, 1936, egg tempera on hardboard panel, 23 5⁄8 x 31 5⁄8 in.

The Schoen Collection: Magic Realism; Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia

One of the earliest works in “Extra Ordinary” resonates especially strongly today. Henry Billings’ egg tempera The Arrest (1936) is a wrenching depiction of police brutality and dehumanization in which uniformed officers and unidentified others in civilian clothes pile on to a suspect of whom hardly anything can be seen except his legs and waist. His head is completely hidden in the scrum, perhaps being fatally harmed. Despite the violence of the encounter, there is something strangely static about it, and the faces that are visible are basically expressionless. The background to the scene has that de Chirico-esque aspect that one sees so often in magic realist paintings. Here, the Classical architecture, viewed incompletely, suggests a courthouse and a public monument, ironically presiding over this purported restoration of public order. As we see in our own time and place, reality can seem unreal when it is most immediate and painful.