Subscribe to Our Newsletter

American Still Life: The Object is the Subject

From scientific specimens to culinary delicacies to mass-produced luxury goods, Americans have always loved stuff, and American artists have responded to that with still lifes in a huge variety of styles.

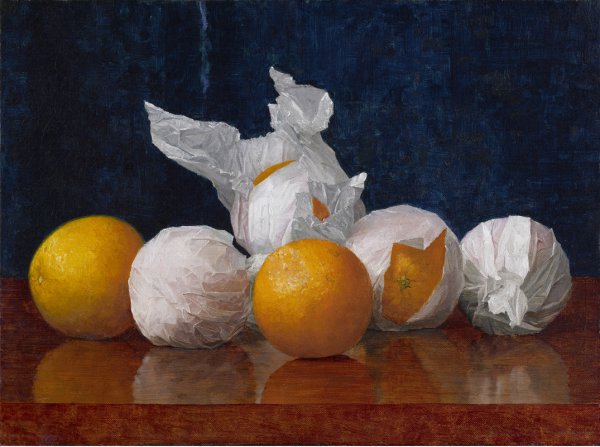

William Joseph McCloskey, Wrapped Oranges, 1889 , oil on canvas , 12 x 16 inches.

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- William Joseph McCloskey, Wrapped Oranges, 1889 , oil on canvas , 12 x 16 inches.

- Charles Whedon Rain, The Magic Hand, 1949 , oil on canvas, 16 x 13 inches.

- Charles Sheeler, Cactus, 1931, oil on canvas, 45 x 30 inches;

- De Scott Evans, Cat in Transit, date unknown , oil on canvas on crate , 10 x 12 x 81⁄2 inches.

- Raphaelle Peale, Venus Rising from the Sea-A Deception, circa 1822 , oil on canvas , 29 x 24 inches.

- Christian Schuessele (Schussele), Ocean Life, 1859 , watercolor, gouache, graphite and gum Arabic on wove paper , 19 x 27 inches;

A still life is a synecdoche: a world in miniature, where one part stands for the whole. The intimate and meditative gaze of a still life renders the familiar strange, and the unfamiliar known: a scientific tableau may juxtapose flora and fauna out of season, and a domestic interior may resound with the echoes of great historical events. Reaching its early apogee in the Dutch Republic, the still life was transformed in another commercial republic, the United States. In the Americanization of the still life, no city was more crucial than Philadelphia, the “Athens of America,” the new nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800 and the home of Charles Willson Peale and his talented progeny. Fittingly, then, the first major exhibition devoted to American still life in three decades opens on October 17 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (on view through January 10).

Curated by Mark D. Mitchell, “Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life” presents the work of nearly 100 American artists, from pioneers like Raphaelle Peale to masters of parlor trompe l’oeil like William Michael Harnett and 20th-century experimenters like Georgia O’Keeffe and Andy Warhol. American still life was born in Philadelphia twice over—first in the early years of the republic, with the Columbianum artists’ association’s show of 1795, to which Raphaelle Peale contributed eight still lifes; and again in the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which represented the United States as a collection of objects. In the intervening century, the young nation grew from an agrarian experiment on the Eastern seaboard into a populous and expansive industrial power. American society was convulsed by civil war and transformed by mass production and mass consumption. In the still life’s attention to natural phenomena and human creations, and in the choreographed interplay of the two, we see time capsules of American history that combine to form a uniquely American narrative.

The first of the exhibition’s four rooms, “Describing, 1795–1845,” depicts two kinds of orientation, toward the raw and the cooked—a scientific self-definition amid the natural world and an artistic self-definition in relation to European precedents. The beer, bread, and cheese of Peter Pasquin’s Frugality (1796) are a republican rejoinder to Old World decadence, but the wine and walnuts of Raphaelle Peale’s A Dessert (1814), with its soft interior light and promise of convivial sophistication, is a confident translation of European luxury to the New World.

The prandial scene of John James Audubon’s House Wren (circa 1824–29) depicts a different kind of abundance on the exterior of the dining room wall. In the great outside of the New World, a hovering hen presents a spider to her chicks as, beaks open, they strain forward from their nest while their father keeps lookout. The scene is both natural and naturalistic, a distillation whose subjects, in the words of Alfred Frankenstein, the early historian of American still life, are “perfectly logical” but also “overtly significant.” These winged American fauna live symbiotically with the two-legged fauna with whom they share a habitat. The description implies the narrative; the images of Audubon’s Birds of America speak the language of scientific universalism but relate the chapters of a unique history, the American discovery of America—which was also the remaking of the natural world. Audubon’s Carolina Parrot (circa 1828) is now extinct. His Eastern Fox Squirrel (1843) scuttles nervously down an invisible branch, as if his environment is giving way beneath him.

The transition to early industrial America was so sudden and violent that none of the artists in the exhibition’s first section appear in its next section, “Indulging, 1845–1890.” Philadelphia now vied with Manchester as the “Workshop of the World.” The modern city was also a center of consumption and display. In 1877, a year after the Centennial exhibition, Philadelphia’s iconic department store Wanamaker’s opened; the same decade saw a new city hall and a new home for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the ancestor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Like the Dutch still life before it, the American still life was remade by a surge of affluence and marketed for the private parlor.

The ideal of plentitude could now be achieved by manufacture and the sensual rewards of nature contrived by artifice, like an overstuffed sofa. In Severin Roesen’s floral still lifes, natural objects are gathered in unnatural combinations, like mail order bric-a-brac from the Montgomery Ward catalog, which debuted in 1872. In Edward Goode’s Fishbowl Fantasy (1867), love letters and a lady’s gloves are cast aside, as though in a romantic melodrama. In Robert Spear Dunning’s 1865 Still Life (With Man’s and Woman’s Hands), the male and female hands indulge in the outrageous sensuality of exchanging ripe fruit. Henry James complained about “a flood of lachrymose sentimentalism” in American art, but this was to miss the point. The flood was less the sentiment than the trappings. The great tide of wealth was lifting the boats of the bourgeoisie and surrounding them with new possessions and experiences.

“As a rule,” William Michael Harnett observed, “new things do not paint well.” He preferred “the rich effect that age and usage gives.” Unlike the artists of his era’s Colonial Revival, Harnett did not present antique objects as sentimental tokens of the nation’s infancy. The objects in Still Life With a Writing Table (1877)—a dictionary, a pen, an inkwell, a blotted letter, a map—are worn rather than old. In Mr. Huling’s Rack Picture (1888), with its assortment of letters and calling cards, the meticulous detail of Harnett’s brushwork creates an illusion of physical presence by asserting endurance over time. The symbiosis here is between Victorian man and his favorite possessions. We see a new social environment and his immersion in it.

In another Harnett oil, The Faithful Colt (1890), a single object stands for epochal public events. Loaned from the Wadsworth Athenaeum Museum at Hartford, Conn., the painting depicts a Colt .44 caliber 1860 Army revolver, hanging from a nail, against a wall of dark green panels. In the Civil War, the revolver was standard issue among Union troops; Harnett called his model “a genuine old Gettysburg relic.” Veterans and their families would have recognized it from the souvenirs hung on their own walls, but by 1890, younger viewers might not have grasped its historical function. When the 24-year-old art critic Paul Weitenkampf saw The Faithful Colt at its first showing in a New York jeweler’s shop, his response was primarily aesthetic—he commented on the “remarkable clearness” of Harnett’s image achieved by illusionistic highlighting, not on the internecine violence of the Civil War.

As in Harnett’s other paintings, the revolver is only worn, not antique. It hangs by its trigger from a loose nail, as though it might spring loose from the wall at any moment. Its weight and gravity, historical or physical, pull against the nail, pressuring the trigger. The war is perpetually present. Three years after Harnett painted this scene of violence remembered and threatened, Frederick Jackson Turner announced the closing of the American frontier. Yet an object designed for killing remains faithful unto death, even when transposed from the open battlefield to a civilian interior. Is the Colt a souvenir on a parlor wall, or is it still on active service, behind a shop counter?

The exhibition’s third section, “Discerning, 1875–1905,” shows how Weitenkampf’s response to The Faithful Colt reflected an age in which photography had altered the terms of realistic representation. As the Pre-Raphaelites had discovered, truthfulness, the exacting depiction of every nuance of surface and texture, could lead to unreality. Henry Roderick Newman’s Fringed Gentian, a Chromolithograph printed after 1867, is as luridly unreal as a plant can be. And if the arresting of nature was unnatural, an art that advertised its technique risked devolving into the parlor game of trompe l’oeil, as in Jefferson Davis Chalfant’s Which is Which? (circa 1897), which challenges the viewer to discriminate between a real and a painted stamp, set side by side.

The connoisseurs tended to prefer the “ideal” alternative, art that communicated a visual impression or emotional state, such as the ethereal, elegant understatement of the French-trained John La Farge’s Wreath of Flowers (1866). The public tended not to. Harnett’s After the Hunt (1885), one of the last great monuments to the twinned still life pursuits of unregenerate blood sports and unapologetic trompe l’oeil, was exhibited over the bar of Theodore Stewart’s saloon in New York City, in a theatrical setting involving red plush curtains.

Is it possible that late 19th-century trompe l’oeil, by advertising its technique and unnatural trickery, represents the low road to Modernist experiment? At times, the “realists” and “idealists” seem to be feuding over a common inheritance and a shared visual language. La Farge’s Wreath of Flowers uses the same illusionistic devices as John Peto’s The Cup We All Race 4 (1905)—both La Farge’s wreath and Peto’s cup appear to hover slightly over the canvas. Similarly, John Haberle, a dab hand at hard-edged trompe l’oeil, also painted conventional still lifes like the delicately misted A Japanese Corner (1898), here complementing La Farge’s Camellia in an Old Chinese Vase on a Black Lacquer Table (1879). Then again, it is the trompe l’oeil realists who, by challenging the viewer to judge what is real, direct the attention away from the object and toward the subjective gaze, whose life is never still. And that is also the implication of the high road to the 20th-century, Cézanne’s perspectivist still lifes.

The exhibition’s fourth room, “Animating, 1905–1950,” shows how still life, a traditional genre, became integral to the Modernist effort to break with tradition and to reflect a society incapable of stillness. In Max Weber’s Chinese Restaurant (1915), a take-out from the Whitney Museum, nothing is fixed. In Stanton Macdonald-Wright’s Still-Life Synchromy (1917), colors clash and planes collide. In Charles Sheeler’s Rolling Power (1939), the locomotive’s wheels are not a still life in the sense of a dead bird. They are temporarily static, like Audubon’s hovering wren and tremulous squirrel. The photorealist detail of their representation is, like Audubon’s paintings, an attempt to catch life on the wing. In this, 20th-century American artists had a home advantage. When it came to the raw material of still life, no other society had produced so many objects or made them so affordable. And as for perspective, no other technological society was so nomadic or so susceptible to isolation and alienation.

The exhibition’s coda brings the story of American still life full circle with the bright ironies of Pop Art and, more precisely, back to Pennsylvania, with Andy Warhol, whose still lifes are more inert than still. In a documentary sense, Pop Art fell within the lineage of earlier representations of ordinary American life and fidelity to historical experience. Raphaelle Peale’s studio might not have contained the industrial materials of Tom Wesselmann’s Still Life #12 (1962), “acrylic and collage of fabric, photogravure, metal, etc. on fiberboard.” Nor did Peale stock his sideboard with such branded delicacies as Coke and Café Bustelo. Still, Peale’s Cutlet and Vegetables (1816) shares Wesselmann’s documentary impulse to record the raw and the cooked in the kitchen of American life. Similarly, in Warhol’s Brillo Boxes (1964), we can see how Pop inherited what Wanda Corn has called the “vernacular bluntness and graphic clarity” of Harnett and Peto. We might add that Warhol inherited Harnett’s challenge to the viewer’s sense of reality, and his showman’s understanding that in trompe l’oeil, the eye enjoys being fooled.

The materials of still life may be simple or humble, but their truths are not. Like any worthwhile journey, “From Audubon to Warhol” returns to a different place. American still life began in a dual orientation, toward a scientific self-definition amid the natural world and an artistic self-definition in relation to European precedents. These final Pop exhibits confirm a unique trajectory, oriented toward self-definition not against nature or Europe, but toward the modern world of American objects.

By Dominic Green