Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Boston Art: Colonial to Contemporary

Boston was America’s first art city, and almost four centuries later, it is still a hub of creativity, art commerce and curatorial clout.

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

Stephen Score kneels in front of an 1830s blanket chest with his hands fanned out against the front. He’s showing me the way a forgotten New England artist used their hands and paint thinned with vinegar to make the watery designs that ripple across the wooden chest.

“This is what’s missing in a lot of folk art paintings that are stiff and brown and what’s missing from some contemporary art, what I call the smoosh quality,” Score says. “Some of the best early folk art, in terms of its line, its abstraction, its emphasis on shape and color, seems almost to anticipate the best of contemporary painting. And that’s one of the things that really and truly excites me.”

We’re in the front room of Stephen Score Antiques, a carriage house in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood, one of the oldest and toniest parts of the city. Score specializes in “deeply artistic, colorful, lyrical objects and paintings with an emphasis on American folk art. … I’m not in favor of anything brown and stiff looking. But I’m all in favor of whimsy.”

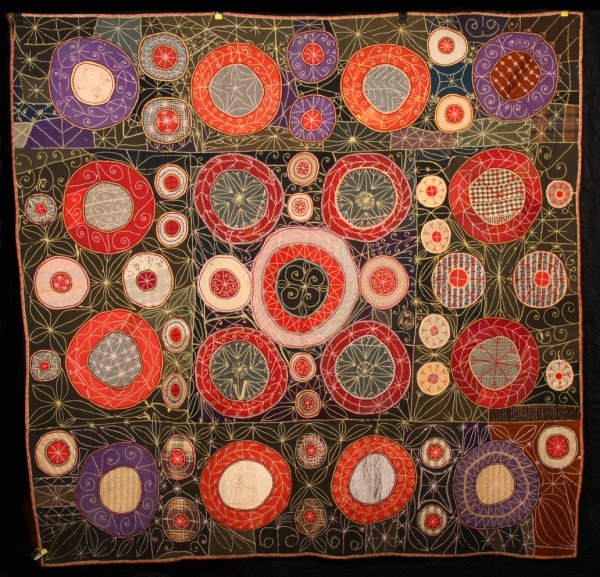

Offerings include an early 19th-century watercolor folk self-portrait, an Art Deco jewelry box shaped like a skyscraper, weathervanes, quilts, hooked rugs and ship paintings. The chest has been acquired by Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Score says. He’s scheduled to deliver it there the next morning.

There are a couple of ways to map Boston’s art scene. If you organize the city by what you can find where, Score’s gallery is a good place to start. You can find history there and at Skinner auctioneers and appraisers, which holds regular sales in Boston and Marlborough, Mass. June auctions feature 20th-century design, fine jewelry and American Indian and tribal art, with highlights including African knives, axes and swords. “African art is such a quagmire of fakes and misrepresentations but these are all clearly authentic and well used,” says Douglas Deihl, director of Skinner’s American Indian and ethnographic art department.

Downtown Boston is compact. It’s a 10-minute stroll southwest from Score’s gallery, through the Public Garden, to Newbury Street, long one of Boston’s gallery districts. More than a dozen galleries operate amid fashion boutiques and restaurants here. It’s the place to go if you want vintage travel posters (International Poster Gallery), prints by Picasso or Warhol (DTR Modern), prints by Kara Walker or a wall of bubbles that Tara Donovan made from tape (Barbara Krakow Gallery), gold leaf drawings and sculptures by Sarah A. Smith (Beth Urdang Gallery), handsome abstractions, and realist painting. (Adelson Galleries, Chase Young Gallery and Soprafina Gallery on Harrison Avenue also feature this sort of art.) For a listing of many of the better galleries in Boston, go to the website of the Boston Art Dealers Association, www.bostonart.com.

On the other side of downtown, at the Boston Center for the Arts’ Cyclorama in the South End, Fusco & Four Ventures presents AD 20/21 (Art & Design of the 20th and 21st Centuries) each March, the Ellis Boston Antiques Show each October and the 17th annual Boston International Fine Art Show in November.

Director Tony Fusco says the Fine Art Show, in particular, has “galvanized the idea that you can collect in Boston. You don’t have to go to New York or Chicago. There’s a world-class show in Boston every November that’s supported by the museums, that’s supported by collectors.”

A sign of Boston’s cultural ambition is the more than $1 billion that has been invested in museum renovations and expansions in the area over the past decade, including the new Institute of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Fine Art’s 2010 Arts of the Americas Wing, and construction at the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge and the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem.

Area colleges—Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Brandeis University, Wellesley College, University, and Boston College—offer museum-level exhibits of international Modern and contemporary art.

The MFA and the Peabody Essex are two heavyweights with encyclopedic collections now operating in similar territory. Both have been exhibiting Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo’s collection of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish paintings (including a Rembrandt), apparently attempting the woo the Marblehead couple to donate the artworks.

The MFA and Peabody Essex by themselves are juggernauts of fundraising. The MFA raised $504 million when it built its new wing. The Peabody Essex has raised more than $570 million toward a $650 million goal. The Salem museum reports that “Upon completion of the [175,000-square-foot] building expansion in 2017, PEM will rank among the top 10 art museums in the nation in terms of gallery space and total endowment and in the top 15 in annual operating budget.”

The MFA’s history is currently being commemorated in an exhibition at the Boston Athenaeum, a library and museum on Beacon Hill. “Brilliant Beginnings: The Athenaeum and the Museum in Boston” (through August 3) celebrates the partnership between the two institutions during the 1870s and 1880s, when the MFA was new and the Athenaeum already seven decades old.

The other way to map the Boston scene is to look at it in terms of art made here. Parallel to Newbury Street is Boylston Street with Copley Square, named for the Revolutionary-era portrait painter John Singleton Copley. Copley’s contemporary Gilbert Stuart, best known for his portraits of George Washington, is buried at Boston Common. Winslow Homer was born here. Fitz Henry Lane began his career here.

At the start of the 20th century, Boston School painters—including Lilian Westcott Hale, Edmund Tarbell, William Paxton and others who studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts—combined an interest in light derived from Impressionism with admiration for the lucid effects of Old Master realism.

Vose Galleries, founded in 1841, resides in a brownstone at the west end of Newbury Street. “We specialize in paintings of the Boston School and New England Impressionists,” says co-director Elizabeth Vose Frey, the sixth generation of the family to operate the business. “American paintings, 18th to mid 20th-century realism. We also have a small stable of contemporary realist artists.”

From June 8 to July 20, Vose offers a survey of Charles Sydney Hopkinson (1869–1962), one of only five Boston artists to exhibit in the infamous 1913 Armory Show that launched European Modern Art in America. His paintings of women on the porch of his home in seaside Manchester, Mass.; yachts riding heavy seas; and a vase of flowers suggest influences from the Ashcan School to American Modernists in Alfred Stieglitz’s circle.

When Boston art people talk about the city’s big contribution to 20th-century art, they often begin with 1930s and ’40s Boston Expressionist painters like Hyman Bloom, David Levine and David Aronson. They were among the “Abject Expressionists”—including Ivan Albright and Leon Golub in Chicago and Rico Lebrun and Edward Kienholz in California—who adopted a realism charged by psychology to reflect their troubled era.

On Newbury Street, you can find paintings by Boston Expressionists Hyman Bloom, Henry Schwartz and Gerry Bergstein at Alpha Gallery and Gallery NAGA. The Museum of Fine Arts gives slight attention to these artists, but the Danforth Art Museum in Framingham has been collecting these artists.

“To me, what happened in Boston in the 1940s and ’50s and even right up to now helps explain what happened in painting in the 20th century. There were real questions about form and where form becomes abstract,” says Danforth executive director Katherine French. “It isn’t that somebody issued a decree in 1952 and everyone started painting abstract. There were a lot of parallel traditions.” French calls this expressionist realism “a missing link” that helps us understand what she sees as a “renewed interest in painting,” an interest in “the impulse of gesture,” bubbling up in art schools and studios today.

The future of Boston art is playing out at the city’s other gallery district, in repurposed manufacturing buildings along Harrison Avenue in the South End, and in outlying spaces. There you might find conceptually-driven installation by artists like Andrew Mowbray (represented by LaMontagne Gallery), Andi Sutton and Jane Marsching; tech art by Denise Marika (represented by Howard Yezerski Gallery), Brian Knep, and Anthony Montuori (at 17 Cox or Boston Cyberarts Gallery); and durational performance at Mobius in Cambridge and Anthony Greaney gallery on Harrison Avenue or organized by Sandrine Schaefer, who co-directs The Present Tense art initiative.

Photography, though, has actually been the area’s most internationally influential contribution to art of the past century—from the scientific experiments of Dr. Harold Edgerton and Berenice Abbott to the Modernist experiments of Minor White in Boston and Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind at the Rhode Island School of Design, an hour southwest, in Providence.

“Boston School” photographers like Nan Goldin made snapshots of the city’s midnight subcultures. Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons performed rituals of her Cuban exile identity in front of Polaroid’s large format camera. Abelardo Morell turned rooms into camera obscuras.

Nicholas Nixon, Frank Gohlke and Joe Deal, who spent significant portions of their careers around Boston and Providence, have been leaders of New Topographics photography of the “man-altered landscape,” the most pervasive style of art photography today. Locals Neal Rantoul, Jim Dow, Barbara Bosworth and Bruce Myren also photograph in this mode.

South of Boston, on Cape Cod, 21st Editions: The Art of the Book publishes hand-crafted volumes that illustrate works of literature with original signed photographs. Their latest title is Imogen Cunningham: Symbolist, with Poetry and Prose by William Morris.

“Boston and Rhode Island have attracted some amazing photographers who are still around and still working very hard,” says Arlette Kayafas, who got to know Edgerton, White, Callahan and Siskind when her husband Gus studied with them four decades ago. No local museum tells this history in a sustained way, but her Gallery Kayafas— as well as Carroll and Sons, Robert Klein Gallery and Panopticon Gallery—showcase many of these local talents, along with other nationally known names like Ansel Adams, Walker Evans, Robert Frank and Alfred Stieglitz.

“I approach a lot of my shows as a collector. When you think about your house there’s often a theme to it,” Kayafas says. She often pairs established masters with young photographers who explore similar ideas, as in her show of Edgerton and Matthew Gamber, which will be on view from June 28 to August 10. The idea, she says, is to showcase “someone who is referencing that work, but doing it differently.”

By Greg Cook