Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Escape to Freedom

Beatrice Mandelman left New York just as it was becoming the center of modern art, but today her unique take on Abstract Expressionism is being rediscovered.

By Edward M. Gómez

When Beatrice Mandelman and her husband, fellow painter Louis Ribak, left New York for New Mexico in 1944, she knew she was leaving behind one of the world’s most dynamic hubs of cultural and intellectual activity—and the possibility of making a lasting mark there. Mandelman could not have predicted that World War II would end the following year, but she certainly knew that New York had become modern art’s axis mundi by the time she decided to move away.

Ultimately, she and Ribak may have paid a price for decamping from the East Coast just as their careers were taking off, but they wanted to distance themselves from what they regarded as the increasing discord between social realists and Abstract Expressionists in New York. Also, one of Ribak’s mentors, the social-realist painter John Sloan, had told him that the Southwest’s climate would be good for his asthma. Relocating to New Mexico allowed both artists to focus on developing their work, despite the fact that they often had to struggle to survive. “Neither of us has had a private income,” Mandelman recalled in 1971. “We’ve made it on our art alone. In the beginning, there were times when we even used to go to the stores and ask for dog bones and then eat them ourselves.”

Now, admirers of abstract art who are interested in the work of less-known American modernists will have a good opportunity to examine a fine selection of both Mandelman’s and Ribak’s artistic production in “Mandelman and Ribak in Taos,” an exhibition of almost two dozen of their paintings that will open at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, N.M., on December 11 and remain on view through February 20, 2011. The pieces are part of a donation of 133 of the two artists’ works from the Taos-based Mandelman-Ribak Foundation to the museum, which is a division of the University of New Mexico. The museum will inaugurate two new galleries for this show, one of which totals 1150 square feet and will be named after the artists. The museum will also be celebrating its completion of a new auditorium and a high-tech system for storing artworks.

Beatrice Mandelman, born in Newark, N.J., in 1912, was the daughter of Jewish parents who had immigrated from Austria and Germany. As an adolescent, she heard about modern art from the artist Louis Lozowick, a Russian-born painter-printmaker friend of her parents who had returned to the U.S. after a stay in Europe, bringing back information about Russian Constructivism. In her late teens, Mandelman began studying at Newark’s School of Fine and Industrial Arts. Through one of her teachers there, she became acquainted with Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky and other artists in New York’s avant-garde.

In the early 1930s, another of Mandelman’s teachers, the painter Bernard Gussow, introduced her to Cubism and other modern-art ideas that had percolated in Europe; in 1935, she was hired by the mural-making division of the Federal Arts Project in the U.S. government’s Works Progress Administration. Later, she took courses at the Art Students League and transferred to a division of the WPA in which she and other artists developed silkscreening techniques. In her earlier works, including her monochromatic lithographs of the late ’30s and early ’40s, Mandelman treated her real-world subjects—a street protest, a dock, a glimpse of a coal-mining town—in a social-realist mode, albeit with Cubist or other modernist elements. In her vibrantly colored silkscreen prints, though, the artist appeared to cut loose. Viewers can see the first stirrings of the more gestural, abstract visual language she would later develop and use to create her signature works.

Mandelman had shown her watercolors and silkscreen prints in exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., by the time she and Ribak, whom she married in 1942, left the East Coast. When they set out for New Mexico, they first headed to Santa Fe, then moved to Taos, where they eventually bought an adobe house with a view of the Sangre de Cristo mountains.

Taos had been a magnet for artists starting at the turn of the 20th century, and the postwar period saw a new influx. Among the older and newer artist settlers living there in the late 1940s and ’50s were Andrew Dasburg, who served as a mentor to many; Agnes Martin, who arrived a few years after Mandelman and Ribak on a University of New Mexico summer-study program and became one of Mandelman’s close friends; and the abstractionists Clay Spohn and Edward Corbett from San Francisco. Friends and associates of these so-called Taos Moderns passed through the town, including such key figures in American abstract art as Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt and Clyfford Still. As the Harwood Museum’s director, Susan Longhenry puts it, “Taos became an extraordinary nexus of artistic expression.”

However, when Mandelman and Ribak arrived in Taos, there were no galleries that promoted modern art, a fact that disappointed the newcomers. So it was that, in 1948, as a local newspaper put it at the time, in reaction against “the traditional ‘aspens and Indians’ brand of painting,” dealer Eulalia C. Emetaz opened the Galería Escondida to show the Taos Moderns’ works. Later, Richard Diebenkorn also came from San Francisco and showed his work at this gallery, even though he was based in Albuquerque, where he earned a master’s degree in art from the University of New Mexico in 1951. In time, Mandelman and Ribak would open their own gallery and their own art school, which they operated until 1953. Among their students were Corbett and Oli Sivhonen, who had studied with Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

From New Mexico, Mandelman and Ribak regularly went on trips to Mexico; they kept a home and studio in the central Mexican town of San Miguel de Allende, which served as a base for further explorations. From her travels in Mexico, Mandelman absorbed a sense of color and history, that she poured back into her art. As for New Mexico, the intense natural light of the American Southwest found its way into her paintings in the form of a radiant, form-defining bright white.

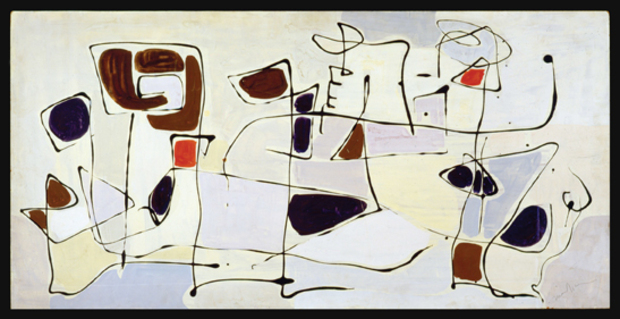

Despite Mandelman’s considerable distance from modern art’s most active centers, her work is noteworthy for its strong affinities with certain artistic developments of its time. Much of it is a fusion of post-Cubist, gestural-abstractionist techniques; much of it is also a record of her experiments with bold, often primary, colors and ambiguously emotive forms. Mandelman’s art could be quiet and meditative in light-toned compositions featuring gentle washes of layered-on color or boisterous and rollicking in paintings like those of her late-career Brazil or Jazz series, with their patches of black and bold, solid hues.

In the 1980s, Mandelman said, “I’m an original. I broke all the rules. I’m using a very primitive language—squares, circles, triangles, primitive colors. And I made a very sophisticated art out of it.” Years later, she added, “I don’t have an external story in my paintings, and that’s difficult for people to accept.”

In recent years, her work has attracted attention from art historians and collectors who are making room in modernism’s canon for overlooked innovators such as Mandelman. New York dealer Gary Snyder, who represents Mandelman’s estate and this past summer presented an exhibition of some of her works on paper from the 1950s and her lateracrylic-on-canvas paintings, says, “Her art is a unique amalgam of influences—from classic Abstract Expressionism to Picasso, Fernand Léger—with whom she studied in Paris in 1948–49—and the Mexican and Native American cultures.” Last month, a selection of Mandelman’s paintings from the 1960s was shown at David Richard Contemporary in Santa Fe, and the Jewish Museum in New York has acquired some of her WPA-era prints. At press time, it was awaiting the confirmation of the promised gift of Canyon, a 1959 casein-and-enamel abstraction on mat board.

Alexandra Benjamin, the head of the Taos-based Mandelman-Ribak Foundation, first met Mandelman a few years before the artist’s death in 1998; Mandelman had hired her to carry out an inventory of her works. Benjamin recalls, “Bea told me before she died, ‘I’ve always had what I wanted—just to be able to go into my studio and paint.’ She was a hard worker, known for her stamina. She painted right up until a week before she passed away.”

Mandelman had a strong sense of herself and her achievements, even if big-name success eluded her during her lifetime. In 1971, after a Taos gallery presented an exhibition of work by women artists that was emphatically ignored by the media, she quipped, “If we’d thrown our bras into the Río Grande, we could have gotten all the attention we wanted.” Later on, she told an interviewer, “My own painting turns me on. I feel it in my heart, the same feeling I get when I hear good music….I’m trying to work from chaos into order, stripping away, using the basics; that part is intellectual. We’re all different, but I think all real artists are working toward the same thing.”

“What’s that?” her questioner asked.

Mandelman replied, decisively, “Freedom.”