Subscribe to Our Newsletter

In Every Fiber

Olga de Amaral harnessed traditional weaving techniques to create highly experimental works of abstraction.

By Sarah E. Fensom

Adobe gris (Gray Adobe), 1976, wool and horsehair

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Ac-cessions Endowment Fund. © Olga de Amaral

The Colombian-born artist Olga de Amaral is one of the most important voices in postwar Latin American abstraction. Known for large-scale pieces that are intricately woven in brilliant color and, frequently, covered in shimmering gold or silver leaf, she’s also a luminary of textile art in general. But her path to fiber art actually began with architecture. That’s what she studied at the Colegio Mayor de Cundinamarca in her native city of Bogotá, Colombia, in the early 1950s. After she received a degree in architectural drafting, she applied to the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Mich. One of the only fields of study Cranbrook allowed students who were not pursuing degrees to undertake was a one-year fabric design and weaving program, so that’s the one she enrolled in. At the Michigan institution, Amaral studied under the Finnish textile designer Marianne Strengell. Strengell had been invited by the institute’s architect, Eliel Saarinen, and architecture factored heavily into her teaching. Strengell encouraged students to treat textiles like a building material and emphasized the industrial design aspects of the medium. This approach brought Amaral’s training full circle.

“Olga de Amaral: To Weave a Rock,” a major touring retrospective of the artist’s six-decade-long career, begins its first leg at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston (MFAH) on July 25. The exhibition features 50 works that, as the museum puts it, “trace Amaral’s architectural investigations of the woven form.” The exhibition is organized with the Cranbrook Art Museum, Amaral’s alma mater, and will travel there after its conclusion in Texas on September 19. It will travel to the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in late 2022.

It took nearly a decade after leaving Cranbrook for Amaral to explore the possibilities of textiles as pure art. When she returned to Bogotá in 1955, she set up an atelier rather than an art studio. There, employing local artisans, she created textiles for architecture and interior design. She also developed a fashion line that produced brilliantly colored neckties, stoles, and mantas guajiras—long, flowy dresses that are traditional in the Guajira region of Colombia. Anna Walker, Assistant Curator of Decorative Arts, Craft, and Design at the MFAH, explains in the exhibition’s catalogue that Amaral designed the mantas guajiras on a square, sketching them on graph paper, with the result that each was a like bold, graphic piece of geometric abstraction.

It was a trip to San Francisco in 1964 that inspired Amaral to start making tapestries. There, visiting the family of her husband (Jim Amaral, the American-born Colombian artist known for his bronze sculptures and drawings), she was encouraged by fellow artists. “Before going to San Francisco,” she told Home Furnishings Daily in 1967, “I wove upholstery and drapery fabrics. Once there, artists persuaded me to try tapestries. First I created tight weaves, then experimented with a loose criss cross technique.” Early tapestries from this period, like Entrelazado en blanco y turquesa (Interlaced in White and Turquoise) (1965, wool) featured strips of gridded color. Their geometric designs and use of fringe were reminiscent of Amaral’s mantas guajiras designs.

Olga de Amaral, Brumas (Mists), 2013, acrylic, gesso, and cotton on wood.

Courtesy of the artist. © Olga de Amaral / Photograph © Diego Amaral

The 1960s was the decade during which Amaral’s career gained prominence and fiber art gained a more radical reputation in the art world. Artists like Lenore Tawney, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Claire Zeisler, Kay Sekimachi, and Sheila Hicks were creating highly experimental works with textiles that used unconventional materials, techniques, and forms. There were a host of international exhibitions during this period that positioned the works of fiber artists as significant entries into the avant-garde, not just pieces of “craft” (the 20th-century artistic canon habitually ghettoized work that employed craft traditions or techniques that could be dismissed as feminine handiwork).

The early 1960s saw the inauguration of the Biennale Internationale de la Tapissierie in Lausanne, Switzerland, an event dedicated to the art of tapestry and more popularly known as the Lausanne Biennial. By its third edition, in 1967, the Biennale had freed itself from a more traditional reading of tapestry—namely that it was by nature pictorial and a form of mural art—and began to incorporate examples of experimental fiber art that abounded with material, dimensional, and textural innovation. In the third Lausanne Biennial, Amaral was the sole representative from a Latin American country at the event. This was a position Amaral would occupy quite often throughout her career. Even though weaving is an integral art form of Andean mountain cultures, the Eurocentric gaze of the art world looked infrequently in that direction. Throughout the Lausanne Biennial’s editions between 1962 and 1993, Amaral was one of only 19 Latin American artists invited to participate.

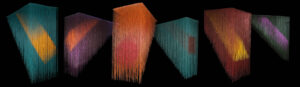

Estelas (Stelae), various dates, linen, gesso, and gold leaf.

Courtesy of the artist. © Olga de Amaral / Photograph © Diego Amaral

In 1969, MoMA featured Amaral’s work in “Wall Hangings,” an exhibition that emphasized a new attitude toward fiber art. The exhibition’s press release called the show “the first major exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art devoted to the contemporary weaver whose work places him not in the fabric industry but in the world of art….” The exhibition featured 28 artists from eight countries, including Hicks, Tawney, Abakanowicz, and others. Its organizers, Jack Lenor Larsen and Mildred Constantine, described them as having “caused us to revise our concepts of this craft and view the work within the context of twentieth-century art.” The 39 pieces in the show were both two- and three-dimensional, installed flat against the wall, hanging from the ceiling, or free-standing as sculpture. They eschewed the “pictorial aspects of weaving” for the “formal possibilities of the craft,” frequently used “conventional weaves” but were worked “free of the loom, in complex and unusual techniques,” and furthermore, utilized methods of construction and materials with a “primary concern to extend the aesthetic qualities inherent in texture.”

The following year, Amaral had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now known as the Museum of Arts and Design or MAD) in New York. The show, titled “Woven Walls,” showcased her series of the same name, or Muros tejidos in Spanish. These highly textured, bulwark-like structures stood freely, emphasizing a new chapter in Amaral’s relationship to architecture. The artist called these pieces “physical structures formed by strips, woven, bound, or wrapped elements in tactile materials such as wool, horsehair, nylon, linen, cotton, and plastic organized in such a way that is very specific and personal.” Like ramparts of the new types of fiber art the MoMA exhibition described, they employed complex techniques, materials, and textures and raised the craft’s formal possibilities to new heights.

The MFAH exhibition features early works from the 1960s, like the aforementioned Entrelazado en blanco y turquesa (Interlaced in White and

Columna en pasteles (Column in Pastels), 1972, wool and horsehair.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund. © Olga de Amaral

Turquoise), as well as Luz blanca (White Light) (1969/1999/2010), a piece from Amaral’s Luz (Light) series (1967–69). In the Luz series, Amaral used plastic, namely polyurethane—a material postwar artists embraced for its versatility and richness of finish and color—exploring the possibilities of synthetics in a textile context. Luz blanca (White Light) and the other pieces of the series showcase the brilliant light that bounces off the material’s surface, creating the effect of a dense, shimmering curtain.

Amaral’s rigorous and highly calculated use of both synthetic and natural materials (like the horsehair, wool, cotton, and linen used in her Muros tejidos, made around the same time as the Luz series) can be traced to the political instability and material scarcity of mid-20th century Colombia. She told American Craft in 1988, “Maybe because my country has been so disorganized, I discovered early on a necessity to organize myself. In Colombia, nothing can be taken for granted. Everything is precious. Nearly all artist supplies, for example, must be imported. Even something as small as a tube of acrylic paint is almost impossible to find.”

Other works dating to the early 1970s in “To Weave a Rock” showcase Amaral’s exploration of form. Columna en pasteles (Column in Pastels), for instance, a wool and horsehair work from 1972, is freestanding and viewed in the round. It exemplifies a quick evolution from Amaral’s Muros tejidos, which began on the wall and then moved to the floor, becoming walls themselves. “By moving her works from the wall, to the floor, to hanging in space, Amaral explores the full sculptural potential of her media,” Walker writes. “When I was doing the woven walls,” Amaral said, “I was creating and dividing spaces with my tapestries. It was my first big creative jump.” Similarly, Columna en pasteles (Column in Pastels) is its own architectural event, bisecting and projecting into the space around it.

Throughout the 1970s, Amaral played with monumental scale, creating architectural works like El gran muro (The Great Wall), a six-story work made for the Westin Peachtree Plaza hotel in Atlanta in 1976. But in the 1980s, she returned to working in a life-size scale, and in many cases her pieces returned to the wall, as well (as in the dazzling Dos columnas moviles or Two Mobile Columns, a wool and horsehair work from 1985). Perhaps, most notably in the 1980s, she began using gold leaf in her pieces, beginning with her prolific Alquimia (Alchemy) series. She was initially inspired by a Japanese vase that had been mended using the kintsugi technique. That method mends cracks and imperfections with the beautifying additions of lacquer and gold. Amaral describes gold as having a “wonderful way of reflecting light” and a magical and mysterious quality. Walker writes that “Colombia’s long and complicated history with gold” is also a consideration in relation to Amaral’s work. “The folklore of El Dorado—whom Spanish colonists described as a mythical leader of the Muisca people, a Colombian indigenous group renowned for exquisite gold work,” writes Walker, “propelled the Spanish to invade the land in search of this precious metal and to exploit and conquer its people. Even today, gold remains a constant presence in Colombian culture and society.”

In Lienzo ceremonial 5 (1989, linen, acrylic, and gold leaf), a standout of the show, gold leaf punctuates a woven “waterfall” of color gradation that seems to rush down the wall-hung piece, terminating in loose, dangling threads. The web of linen threads that Amaral intricately weaves together sits on top of a gessoed and painted background. These compositional elements create the sense that Amaral’s woven threads are an abstract action happening on a canvas-like surface. They in turn also activate the wall on which the piece is hung, making it a dynamic setting. Works like Prosa I (Sol Blanc I), or Prose I [White Sun I] (1993, linen, gesso acrylic, and gold leaf) use gold leaf almost to hint at pictorial details—in this case a bisected circle that has a solar connotation. Later wall-hung works, like Pueblo V (Town V), a linen, gesso, acrylic, and gold leaf piece from 2013, and Alquimia 003 (Alchemy 003), a linen, gesso, acrylic, and gold leaf piece from 2014, are like curtains of solid gold. They almost have the qualities of finely woven gold chains, which pick up and reflect light in abstract, unpredictable ways. In a gallery setting, light reflects off these golden works, projecting flecks of light on the surrounding walls, like avant-garde disco balls.

Olga de Amaral, Lienzo ceremonial 5, 1898, linen, acrylic, and gold leaf.

Courtesy of the artist. © Olga de Amaral / Photograph © Diego Amaral

Pieces like Bosque I y Bosque II (Forest 1 and Forest II) prompt unexpected movement in the gallery setting, as well. In the rich green diptych, long threads twist and float off the wall with the movements of air. The threads, which hang from two back panels of wrapped horizontal cords, are painted to suggest a tilted square that’s divided among the diptych’s two panels. In Agujero Negro (Black Hole), a 2016 linen, gesso, and acrylic work, a black void appears to be painted on a sheet of gray fringe. However, as viewers pass by, its threads waft, revealing a sliver of gold paint that gleams in the light.

Though many of Amaral’s works of the 1990s and 2000s are hung against the wall, she continues to experiment with innovative forms. In the works of the Nudo (Knot) series, for instance, long linen fibers are hung from the ceiling. The loose threads are twisted in one big knot, creating the look of a giant tassel. The MFAH show includes Nudo 19 (Turquesa) or Knot 19 (Turquoise), a shimmering blue-green work dating to 2014, and Nudo 25 (Magenta) or Knot 25 (Magenta), a deep pink rendition from 2015.

Estelas (Stelae), another standout of the show, is an immersive series of works from various dates. The suspended structures are made of individual woven squares that have been stiffened with gesso. Oriented together in groups, their fronts are covered in gold leaf, making them reflective and mineral-like. Amaral’s Stelae are inspired by upright stone slabs of the same name that are often made for commemoration. The artist, Walker explains in her catalogue essay, has several stelae installed in the front yard of her country house in Bogotá. “Their surfaces,” writes Walker, “are textured with various lichen and plant life, and their shape is representative of the fiber works of the same name.” In a 2003 lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art titled “The House of My Imagination,” Amaral said that the Stelae “retook some ideas of the free-standing, large-volume fiber structures I had made during the late seventies and early eighties. . . . But now I had squeezed volume materially into a lithic surface. I think of them as stones full of space, each one a presence full of secrets. Many together, like mounds of stones or rocks, point to an answer, an unknown order, a hidden history.”

Observing the Stelae, the viewer is so enamored with their structural integrity and sense of pure abstraction that it’s easy to forget that their existence is owed to the incredible intricacy of Amaral’s woven materials and her methodical experimentation with traditional weaving techniques. They’re works of textile that fuse architecture and nature into a new structural phenomenon. In the catalogue for a 1996 installation of Stelae at the Fresno Art Museum, Amaral wrote, “Space has [a] relationship to tapestry. My tapestries belong to walls. They exist. I want them to feel like a presence, but I don’t want that presence to be an intrusion. I want them to become almost transparent. To be presence, to be wall, and to be weightless, floating, ingravido.” Amaral said that she wanted to “achieve a sense of floating in space” as though “memory were suspended in a mystical space.”