Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Murder the Moonlight

The Guggenheim gives Italy’s feisty Futurists their first comprehensive show in America.

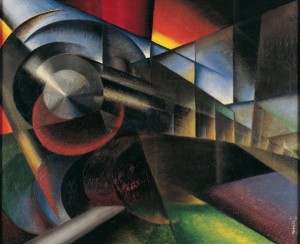

Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train (Treno in corsa), 1922, oil on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- Umberto Boccioni, Elasticity (Elasticità), 1912, oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm;

- Gerardo Dottori, Cimino Home Dining Room Set, early 1930s;

- Ivo Pannaggi, Speeding Train (Treno in corsa), 1922, oil on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

- Tullio Crali, Before the Parachute Opens (Prima che si apra il paracadute), 1939, oil on panel, 141 x 151 cm;

When the Futurist movement launched itself in 1909, its founders could little have imagined that their first museum exhibition in the United States, the world’s most future-oriented country, would be 105 years in the future. The delay was due in part to Futurism’s association with Italian fascism, which tarnished its reputation in the democratic world. But while time may not heal all wounds, it at least provides some perspective, and from the vantage point of 2014, Futurist art still looks, well, futuristic. Visitors to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York can see for themselves in “Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe,” a long-running (through September 1) massive, 360-work show that features not only painting, sculpture, and photography but also literature and paper ephemera, design objects, film, music, and documentation of theater and other performances. From the beginning, Futurism was a multimedia movement, and its members believed that art and life could not and should not be separated.

The official founder and guiding spirit of Futurism was not a visual artist at all but a poet, F. T. Marinetti, and at first it was primarily a literary movement. Fittingly, it announced its inception with a manifesto, in 11 bulleted points. Among them were the following: “Up to now literature has exalted contemplative stillness, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt movement and aggression, feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the slap and the punch….We affirm that the beauty of the world has been enriched by a new form of beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car…is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace….We intend to hymn man at the steering wheel, the ideal axis of which intersects the earth.” When this manifesto, bold as it was, failed to generate as much furor as he had hoped, Marinetti issued a second one titled “Let’s Murder the Moonlight.” Before long, the slap and the punch became literal realities, as the Futurist youth traded blows with the public and the police at outrageous events called serate that were part lecture, part performance piece, part riot.

Intoxication with speed came naturally in the country that gave the world the Bugatti and the Ferrari. The hyperkinetic Marinetti himself was dubbed “the caffeine of Europe”—fittingly, the Guggenheim show is underwritten by Lavazza—and his mercurial nature mirrored the contradictory character of Futurism itself. He was an Italian super-patriot but was born in Egypt, lived for a long time in Paris, and wrote originally in French. He celebrated youth rebellion but became an establishment figure, decorated by the Mussolini government. He could be comically absurd, as when he exhorted Italians to give up lethargy-inducing pasta in favor of molded, scientifically processed, ozone-scented “Futurist food,” but he had a genuine critical sense, and the art he inspired and organized was anything but ludicrous. Futurism’s own internal ironies included the fact that it celebrated the common man, claiming that art was for all and should be made by all, even collectively, and yet the tone of its publications was often elitist and its artworks the products of refined technique.

Another irony, notes Guggenheim curator Vivien Greene in a catalogue essay, is that Futurist art celebrated the machine but was itself anything but mechanical. For all its preoccupation with technology, Futurism’s most characteristic medium was good old-fashioned painting, not photography or cinematography. The most important painters among the original cadre of Futurists are Umberto Boccioni, Gino Severini, Carlo Carrà, and Giacomo Balla. Their style can closely resemble Cubism, which was being developed contemporaneously by Picasso and Braque, and indeed the Futurists were often accused of copying the Cubists. However, there are important differences between the two schools of art. Cubism was largely static, an analysis of spatial relations, its preferred subject the still life; Futurism was dynamic, and its analysis was applied to time.

Like the Cubists, the Futurists created fractured, prismatic, or kaleidoscopic images, but their intention was to show many moments all at once—or, at the very least, to convey speed in an unmoving picture. In a 1911 triptych, Boccioni depicted the states of mind that occur at a train station, the first panel being devoted to the process of seeing people off, the second to the people departing, and the third to those left behind after the train has gone. In Balla’s The Hand of the Violinist (The Rhythms of the Bow) (La mano del violinista [I ritmi dell’ archetto]), 1912, we see the musician’s hand and the scroll of the violin repeated several times in the triangular canvas, blurred by motion. The brush strokes are short, repeated lines of red, yellow, and green that combine to convey the color of the hand.

This technique reveals Futurism’s deep roots in Divisionism. The vibrating dots and dashes of Divisionism, originally intended to break color down into its components, here take on a more kinetic role, conveying the pulsation of nervous energy. Many Futurist paintings, such as Boccioni’s astonishing Elasticity, are rich in rainbows, and looking at them, one starts to feel frequencies, speeds of electromagnetic vibration, rather than simply hues.

The Guggenheim show is unique in that it represents the whole course of Futurist history, not just the first, pre-World War I “heroic” phase that is best known. After the war, the movement became more explicitly focused on mechanical devices as subjects and sources of inspiration, and in the 1930s, a gentler, less hard-edged look became popular. The movement moved from Milan to Rome, and a new crop of younger artists got involved, such as Julius Evola (also known as an occultist, a writer on Hermeticism and Buddhism, and a mountaineer) and Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, F. T. Marinetti’s wife, who was known professionally simply as Benedetta. Among the treats at the Guggenheim are a series of murals Benedetta made on commission from the Italian post office, which depict, in a Deco-tinged style, various means of modern high-speed communication and transportation. The inclusion of women artists and writers in the show makes it clear that while much Futurist rhetoric was antifeminist to say the least, in actual fact the case was less clear-cut.

One of the most remarkable discoveries of the exhibition is the late-Futurist genre of aeropittura, or aerial painting. Mechanized flight has a powerful imaginative component that has always made it more than mere transportation. As far back as 1909 the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, a major inspiration to the Futurists, had been taken for a very brief, low-altitude spin by the American aviator Glenn Curtiss at an air show in Brescia. Upon landing, D’Annunzio proclaimed flying “divine and yet inexpressible.” In the last phase of Futurism, during the 1930s and early ’40s, depictions of flight became very prominent. One of the most memorable paintings in the Guggenheim show is Tullio Crali’s Before the Parachute Opens (Prima che si apra il paracadute), from 1939. Here we are given a radically fresh view of the world, floating directly above a parachutist, looking down at the clouds. The man’s outstretched arm blends into a curving line of shadow that draws the eye to a vanishing point that is not at the horizon, where it usually is, but straight down on the ground. The representation is basically literal; there’s not much here in the way of Cubism or Divisionism. Crali lets the scene itself supply the Futurism; where he places us, we have no choice but to feel the speed and to experience the fear and thrill of entering the unknown while trusting only in technology and oneself. The journey into the future becomes a free-fall.