Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Print Culture

Japanese printmaking and photography of the 20th century would be unthinkable without each other.

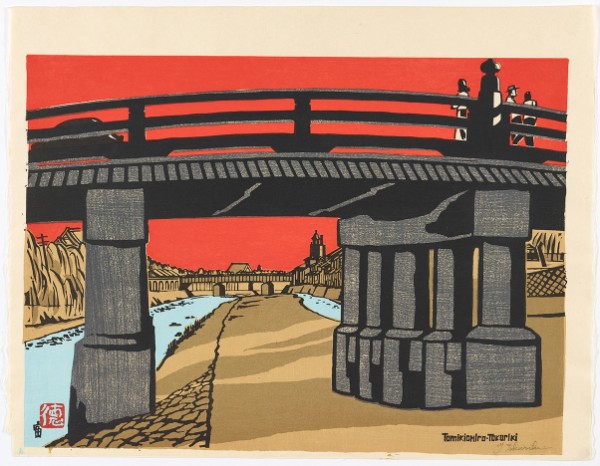

Tokuriki Tomikichiro, Sanjo Bridge, 1954 , woodblock print; ink and color on paper.

- Tokuriki Tomikichiro, Sanjo Bridge, 1954 , woodblock print; ink and color on paper.

- Kawase Hasui, Ferryboat Landing at Tsukishima, from the series Twelve Months of Tokyo, 1921, woodblock print; ink and color on paper

- Ohara Koson, Evening Scene with Sail Boats and Mt. Fuji, 1900s, woodblock print; ink and color on paper.

- Moriyama Daido, Evening View, 1977, chromogenic print

Japan has been in love with photography ever since the mid-19th century, when the advent of the new European picture-making invention coincided with Japan’s opening up to foreign influences under the Meiji Restoration. The new word coined for photography was shashin, meaning “reproducing truth,” and early Japanese photography tended to be documentary in nature. Often using hand-applied color, photographers filled many of the same functions as color woodblock prints, but at lower cost and with the added attraction of novelty. For these reasons, the rise of photography was one of the most important factors (along with the newspaper printing presses) in the demise of the traditional ukiyo-e print, which by the end of the 19th century was left without a market and therefore without creative energy. When Japanese printmaking experienced a rebirth about 20 years later, it was in new formats and styles, all of which had to acknowledge the fact of photography, either as an influence or as something to define itself against. Meanwhile, after World War II and especially in the ’50s and ’60s, Japanese photography experienced a rebirth of its own, with the rise of the Japanese camera industry and, in parallel, a new spirit among photographers who eschewed simplistic documentary in favor of a radically poetic way of portraying the social changes in Japan at the time.

Many of these trends and forces can be seen and studied in a pair of complementary exhibitions now on view at the Freer | Sackler at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. The Asian art galleries are celebrating the acquisition of one of the most important collections of Japanese photography by putting around 70 photos on view in the exhibition “Japan Modern: Photography from the Gloria Katz and Willard Huyck Collection” (September 29, 2018–January 21, 2019). Concurrently, the museum will also mount “Japan Modern: Prints in the Age of Photography,” which examines the new printmaking media and aesthetics that arose around 1920 and continue to be vital to this day.

Although the Katz–Huyck collection includes works dating back to the 1880s, the ones on view in “Japan Modern” span the 1930s through ’80s, the period in which Japanese photography really came into its own as an innovative, creative force. One of the first photographers of this period to make an impact was Shoji Ueda, who absorbed the influence of European Surrealism in the ’30s and ’40s and expressed it in a completely local and personal way. Ueda made a specialty of photographing people against the sand dunes in his home town of Tottori. In these dune photos, the human figures seem to become dislocated, intentionally placed in a surreal space where they acquire a mysterious, elusive new meaning, as in My Wife on the Dunes (circa 1950). In his Boku To Neko (The Cat and Me) (circa 1950), Ueda takes a traditional ukiyo-e theme, a person playing with a cat, and gives it a slightly absurdist feel, partly by placing it incongruously outdoors and partly by making it a comic-strip-like triptych that defeats our expectations that it be chronologically sequential.

Eikoh Hosoe, one of the greatest names of modern Japanese photography, is well represented in the exhibition. Starting out as a photographer after Japan’s catastrophic defeat in World War II, Hosoe explored psychic realms of darkness and eros, often through performance-art collaborations with other artists, including the writer Yukio Mishima. In Simmon: A Private Landscape (#1) (1971), Hosoe poses the actor Simon Yotsuya in a field of weeds with power lines in the far distance. Yotsuya, wearing heavy makeup and a kimono-like robe, looks like a courtesan out of ukiyo-e transported to a postindustrial landscape. Some of the other photos in the show, such as Seikan Ferryboat (1976) from Fukase Masahisa’s “Ravens” series, channel some of the angst and craziness of atom-bomb-scarred postwar Japan. Tomatsu Shomei’s Yokosuka, Kanagawa (1959) conveys a sense of fragmentation through multiple points of view and distorted optics. These are all black and white images; when color is used, the connection with Japanese printmaking comes through clearly. Hamaya Hiroshi’s glowing, reddish-orange Cibachrome Peaks of Takachiho Volcano (1964) is in a lineage going back to Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji. Daido Moriyama’s Evening View (1977), an atypically serene image for the edgy photographer, isolates a red light bulb against a deep blue, almost dark sky in a way that suggests the lamps in 19th-century prints.

In making the connection between printmaking and photography, it is important to remember that in Japan, which did not have robust gallery and museum scenes for photography, the medium was promoted largely through magazines such as Camera Mainichi and Provoke and through photobooks, the latter a genre in which the Japanese have always excelled, and still do. Prints and photographs are both multiples, media invented for the purposes of infinite reproduction, and therefore each has a deep connection to the enterprise of publishing.

The “Japan Modern” print exhibition consists mainly of landscapes, and across a variety of styles they show how powerful the influence of photography was on printmakers. Ferryboat Landing at Tsukishima (1921), from Kawase Hasui’s series “Twelve Months of Tokyo,” is an example of shin hanga (“new prints”), the luxurious and technically polished school of woodblock printmaking that arose from the ashes of ukiyo-e. Hasui shows us the boat through an opening between pillars at the dock, looking upward, and the composition of this image strongly suggests the way a camera lens sees it. Despite the exquisite refinement of the line and color, this print has a snapshot aesthetic. Tile Roof (1957), by Sekino Jun’ichiro, is from the school of sosaku hanga or “creative prints,” a rougher-around-the edges set of styles that required the artist’s involvement in every stage of the process, unlike the traditional schools in which technicians would work from an artist’s designs. The tightly cropped view downward onto the roof makes the scene almost abstract, an effect typical of modernist photography. This particular image is reminiscent of some of André Kertész’s photographs. In Kimura Risaburo’s City 119 (1969), the vantage point is pulled up so high that the woodblock print resembles an aerial photograph. And some of the prints, such as Ono Tadashige’s Road (1954) or Kawanishi Hide’s Kobe Port (1953), use deliberately crude techniques and non-realistic color schemes as if to say, here is something that a photograph cannot do; this is not shashin.

—

By John Dorfman