Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Kings of Collecting

Portrait of the Collector of Modern Russian and French Paintings, Ivan Abramovich Morozov, 1910, tempera on cardboard, 63.5 x 77 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Artworks once owned by the wealthy Morozov brothers of Moscow, pioneering collectors of modernism in the early 20th century, are being seen outside Russia for the first time.

By Sarah E. Fensom

The famed Moscovite brothers Mikhaïl and Ivan Abramovich Morozov brought an astounding amount of masterpieces from Western Europe to Russia, creating collections of seemingly limitless depth.

When Mikhaïl Abramovich Morozov lost a million rubles in one evening playing cards at the English Club, all of Moscow was captivated. At 21, Mikhaïl had inherited his share of millions from his family’s textile empire—an operation that his great-grandfather Savva, a serf, grew from the five ruble-dowry his wife brought to their marriage. The gambling loss was just another flourish of Mikhaïl’s famed extravagance. The mansion he purchased on Smolensk Boulevard in 1891 had an Egyptian antechamber that featured a bizarre juxtaposition of old and new technology, with a sarcophagus, an authentic mummy, and a telephone. It was an open secret that Rydlov, the ambitious and vain protagonist of Alexander Sumbatov-Yuzhin’s 1897 play The Gentleman, was based on Mikhaïl.

A fin de sìecle it-boy surrounded by luxury, art, literature, and philanthropy since birth, Mikhaïl didn’t want or need to limit himself. He ran for various public offices and gave generously to cultural and civic causes. In 1894, he published two monographs, one on Charles V and the other about scientific controversies in Western Europe. In 1895, he published Into the Darkness, a serious novel, of which the Committee of Ministers destroyed the entire print run (characters bore suspicious resemblances to Russian dignitaries). Mikhaïl’s art criticism appeared in several contemporary journals and included feisty yet reasonable stabs at artists like Valentin Serov.

Valentin Serov, Portrait of Mikhail Abramovich Morozov, 1902, oil on canvas, 216 x 81.5 cm

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Serov, along with Konstantin Korovin and Mikhail Vrubel, were part of a group of artists that regularly met at Mikhaïl’s mansion starting in the early 1890s. Mikhaïl didn’t just surround himself with artists, he collected liberally, typically buying Russian pictures from exhibitions or directly from painters. His purview quickly expanded abroad—Paul Albert Besnard’s Féerie intime (1901) and Jean Veber’s Lutte de femme dans le Devonshire were the first Western paintings he purchased (he turned the Veber around quickly, but the Besnard stayed in his collection). Over the course of roughly eight years, Mikhaïl procured an enormous wealth of important paintings, including significant works by the Impressionists, Post-impressionists, Nabis, and Symbolist painters. When Mikhaïl died in 1903 at just 33, he was at the height of his collecting prowess. His widow Margarita Kirillovna, a highly active figure in Moscow society, donated 60 works of her husband’s 83-painting collection to the Tretyakov Gallery, keeping only the family portraits and a few personal favorites for herself. It was through this gift that Mikhaïl’s incredible cache of Western European paintings entered a public gallery in Russia.

Mikhaïl’s younger brother Ivan Abramovich Morozov, born just one year later in 1871, followed in his sibling’s footsteps as a collector. His path, however, began as an artist—he studied painting under Korovin and traveled with the artist Iegor Khruslov on the Volga and throughout the Caucasus. A preternatural businessman, he eventually gave up painting to study chemistry in Zurich. He was away from Moscow during much of his brother’s heyday in the 1890s, but when he returned to the city in 1900, he started purchasing Russian paintings for his mansion on Prechistenka Street. He began with artists Mikhaïl had collected—Korovin, Serov, Levitan, Vrubel, Aleksandr Golovin, Konstantin Somov, and Alexandre Benois—but soon added works by Marc Chagall, Pavel Kuznetsov, Mikhail Larinov, Aleksandr Kuprin, and Ilya Mashkov, among others.

Like his brother, Ivan set his sights on works by foreign artists. Around 1903, he acquired two exuberant works by Spanish painters—La Fabrication des raisins secs (1901) by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida and Préparatifs pour la course de taureaux (1903)—but thereafter, his focus was entirely on the work of the French.

For Ivan, the pivot into Francophilia began with the purchase of Alfred Sisley’s La Gelée à Louveciennes (1873) in 1903. He enlisted the help of painter Sergei Vinogradov, Mikhaïl’s former advisor, and purchased a work by Camille Pissarro (Terre labourées, 1874) from Ambroise Vollard in 1904 and several more works by Sisley from Paul Durand-Ruel in 1904 and 1905. Ivan contemplated buying his first Monet for a year, but eventually purchased Waterloo Bridge. Effet de brouillard (1903). He began collecting works by Renoir—eventually acquiring six—and Pierre Bonnard—he bought Paysage du Dauphiné (1899) and Coin de Paris (circa 1905) in 1906 and eventually added more than 10 others to his collection. In 1906, Ivan’s involvement with the Salon d’Automne also grew, with the collector donating works to a Russian art exhibition and receiving an honorary membership and the Order of the Legion of Honor.

Ivan bought Maurice Denis’ Source sacrée à Guidel (1905) along with the Bonnards in 1906. A few years later, he commissioned a series of mural panels from the artist for his music room. The mythological works tell the story of Psyche and are rendered in flat blues and pinks in a style reminiscent of Art Nouveau. Denis introduced Ivan to Aristide Maillol, who created four bronzes for the music room. Maillol became Ivan’s favorite sculptor, and the collector acquired six small bronzes, as well.

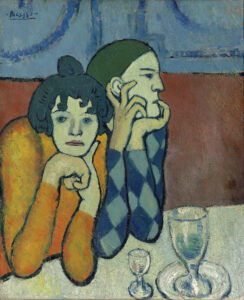

Pablo Picasso, Les Deux Saltimbanques, 1901, oil on canvas, 73 × 60 cm.

Pushkin Museum, Moscow © Succession Picasso 2021

A pivotal year for Ivan was 1907, which can be seen as the approximate period he stepped out of his brother’s shadow as a collector. That year saw his marriage to the singer Yevdokiya (Dosya) Kladovshchikova. It also saw the expansion of the galleries within his mansion, with contemporary French paintings taking center stage over the Russian pictures and providing a sweeping view of the last 30 years of avant-garde art. The collector added four Monets, three Renoirs, and his first works by Gauguin and Cézanne that year. He bought Gauguin’s MATAMOE (La Mort). Le paysage aux paons (1892) first before adding eight more canvases by the artist in hardly a year (he would go on to acquire 11 total by the artist). In time, Ivan hung Gauguin’s Café à Arles (1888) in his galleries next to Le Café de nuit (1888) by Vincent Van Gogh, Gauguin’s companion in Arles during the autumn of 1888. Ivan began collecting Van Gogh in 1908, adding Les Chaumières (1890) to his cache first.

In 1907, Ivan also, like many others in France and throughout Europe, fell hard for Cézanne during the posthumous retrospective of the artist at the 1907 Salon d’Automne. He bought four Cézanne canvases on the spot, before eventually acquiring 18 works by the master (six of which were purchased from Vollard in 1911–12). Ivan referred to Cézanne as his favorite artist, and at the beginning of the 20th century, the collector had the finest collection of his work in the world. One of Ivan’s particular favorites, Paysage bleu (circa 1904–06), exemplifies the collector’s discerning approach. Art critic Sergei Makovskii wrote of an empty space in a gallery wall of Ivan’s that was otherwise covered in Cézannes. “‘It’s for Le Cézanne bleu [a landscape from Cézanne’s first period],’ Ivan Ambromovich explained. ‘I’ve wanted one for a long time, but I can’t make up my mind.’ The space stayed empty for more than a year, and it was only recently that a magnificent ‘blue’ landscape chosen from among dozens of others was hung alongside the other lucky ones.”

Matisse, too, found his way into Ivan’s collection in 1907, with the collector’s purchase of the young artist’s Bouquet (Vase aux deux anses), painted that year. Ivan, typically a methodical, if hesitant, collector focused on acquiring bona fide works, rather audaciously acquired a number of Fauvist works early in the movement’s foundation. These included Maurice de Vlaminck’s Vue de la Seine (circa 1906) (which Vollard threw in as an extra among a group of other paintings Ivan was buying), André Derain’s standout Le Séchage des voiles, and Jean Puy’s L’Été (1906).

Henri Matisse, Fruit and Bronze, Issy-les-Moulineaux, 1910, oil on canvas, 91 × 118.3 cm.

Pushkin Museum, Moscow © Succession Ivan Morozov, Henri Matisse

Ivan commissioned Matisse to paint murals for him in 1911. These works, the jewel of Ivan’s 11 Matisse canvases, became known as the Moroccan triptych. The artist painted these three canvases—La Vue de la fenêtre. Tanger, Zorah sur la terrasse, and La Porte de la Casbah (late 1912–early 1913)—in the open air in the gardens of Tangier. Ivan collected Picasso, too, if conservatively. He acquired only three canvases by the artist: Les Deux Saltimbanques (1901), Picasso’s first work in Russia; the rose-period Acrobate à la boule (1905), which was previously owned by Leo and Gertrude Stein; and the Cubist Portrait of Ambroise Vollard (1910).

Ivan’s collecting was interrupted by World War I and then, even more severely, by the Bolshevik coup. In December 1918, it was nationalized. Morozov was appointed “assistant curator” to the collection, which had never been shared with the public before. In 1920, Ivan and his family left clandestinely for Riga, and then Paris. Switzerland was the family’s planned destination, but Ivan took ill in Paris in the spring of 1921. He died that year in Carlsbad at the age of 49. The Bolshevik government renamed Ivan’s collection the State Museum of Modern Western Art / GMNZI. Opened in Ivan’s Moscow mansion in 1928, it became the first museum of modern art in the world. Between the 1930s and 1948, Mikhaïl and Ivan’s collections were spread out among the State Hermitage Museum, the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, and the Tretyakov Gallery.

Legendary critic Félix Fénéon described Ivan’s collecting habits in Paris thus: “Barely off the train, he settled himself into the easy chairs of the art galleries … the ones that are deep and low, so the collector did not have to get up to see the succession of paintings that were passed before him like frames of a film. Having engaged his particularly discerning eye, Mr. Morozov was too tired in the evening to even to go to the theater. After days at this pace, he left for Moscow having seen only paintings, taking a few chosen pieces with him.” Morozov, who also religiously visited the salons in the spring and fall, often acquired more than a few chosen pieces on his visits. In some years, like 1907 and 1908, he purportedly returned to Moscow with more than 60 canvases. Ivan collected Western art for more than 10 years, and is said to have acquired 278 paintings, dropping 1.5 million francs in doing so.

Paul Gauguin, Eu haere ia oe (Où vas-tu?), 1893, oil on canvas, 92.5 x 73.5 cm.

Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Soon the Morozov Collection will travel outside of Russia for the first time since its formation. Its destination is the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris (the exhibition, titled “The Morozov Collection,” was slated to open in May, but has been delayed due to the global pandemic and resulting lockdown in France). The show, which is being presented in partnership with the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts (Moscow), the State Hermitage Museum (Saint Petersburg), and the State Tretyakov Gallery (Moscow), brings together 200 masterpieces of French and Russian modern art with important loans from the State Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg, the National Art Museum of the Republic of Belarus (Minsk, Belarus), the Dnipropetrovsk Art Museum (Ukraine), the MAGMA Moscow, and the private collections in Moscow of Petr O. Aven and Vladimir and Ekaterina Semenikhine. It boasts an almost unfathomably rich roster of artists, including Manet, Rodin, Monet, Pissarro, Toulouse-Lautrec, Renoir, Sisley, Cézanne, Gaugin, Van Gogh, Bonnard, Denis, Maillol, Matisse, Marquet, Vlaminck, Derain and alongside Russian masters including Repin, Vrubel, Korovin, Golovin, Serov, Larionov, Goncharova, Malevich, Mashkov, Konchalovsky, Outkine, Saryan and Konenkov.

The show is the second in the Fondation Louis Vuitton’s Icons of Modern Art series organized alongside the trilogy of Russian museums. Its predecessor, “Shchukin Collection,” was held in 2016 and attracted a record-breaking 1.3 million visitors. That exhibition focused on Sergei Shchukin, a Muscovite industrialist, and patron and collector of famous works of Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism, who was also a friend of the Morozovs. Like that of the Morozovs, Shchukin’s collection was also seized, nationalized, and broken up in the wake of World War I and the October Revolution.

The exhibition features several impressive portraits of the collectors and their families, such as Serov’s imposing, full-length Portrait of Mikhail Abramovich Morozov (1902) and sensitive Portrait of Mika Morozov (1901), Mikhaïl’s young son. Serov’s Portrait of the Collector of Modern Russian and French Paintings, Ivan Abramovich Morozov (1910) is especially exciting, as it pictures Ivan with Matisse’s Fruits et bronze (1910) behind him.

The show also includes many of the pivotal acquisitions from the brothers’ collections. Renoir’s sublime Portrait de Jeanne Samary. Rêverie (1877), a jewel of Mikhaïl’s Impressionist painting collection, comes to the exhibition from the Pushkin Museum. Edvard Munch’s Nuit blanche. Osgarstrand (Filles sur le pont) (1903), also from the Pushkin Museum, was among Mikhaïl’s most exciting Western art purchases from a non-French artist. Van Gogh’s La Mer aux Saintes-Maries (1888), an energetic post-Impressionist seascape, also travels from the Pushkin.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait d’Ambroise Vollard, 1910, oil on canvas, 93 x 66 cm.

Pushkin Museum, Moscow © Succession Picasso 2021

Sisley’s La Gelée à Louveciennes (1873), Ivan’s pivotal first purchase of a French work, finds pride of place in the show, as does his first Monet Waterloo Bridge. Effet de brouillard (1903). Nature morte à la draperie (circa 1892–94), a pensive yet engrossing still life by Cézanne, represents Ivan’s sterling collection of the artist as well. It comes to the show from the Hermitage Museum. Gauguin’s richly colored MATAMOE (La Mort) (1892) joins several other works by the artist in the show. Picasso’s Acrobate à la boule (1905) and Portrait d’Ambroise Vollard (1910) are on view, as well.

The exhibition also presents the Music Room from Ivan Morozov’s Moscow mansion for the first time outside of the State Hermitage Museum. There, the seven panels of Denis’ The Story of Psyche will be presented as will the four commissioned bronze sculptures by Aristide Maillol.