Subscribe to Our Newsletter

La Belle Époque: Poster Pioneers

The French Belle Époque brought the world the fine-art advertising poster, creating a collecting mania that hasn’t subsided since.

Alphonse Mucha, Cycles Perfecta, 1902.

- Alphonse Mucha, Cycles Perfecta, 1902.

- Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Motocycles Comiot, 1899;

- Alphonse Mucha, Princess Hyacinth, 1911

- Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, La Rue, 1896.

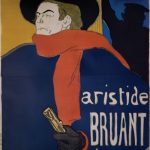

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Ambassadeurs Aristide Bruant dans son Cabaret, 1892.

She leans over her bicycle like a queen surveying the lands that she rules. She needs no crown; her hair is crown enough. It radiates from her head in dreamy, curling tendrils that show that reality has no power in her world. Her locks arc, waft, and splay in every direction, and yet they somehow avoid tangling themselves in the spokes of her front wheel. The legend above her head reads “Cycles Perfecta,” but the artwork leaves no doubt that she is the perfect one here.

Czech-born artist Alphonse Mucha signed the Cycles Perfecta poster in its lower right corner, but he didn’t need to. Only his women look like the nameless tousle-headed bicyclist. Starting on February 11, she will grace the landing of a staircase at the Driehaus Museum of Chicago, as part of the exhibition “L’Affichomania: The Passion for French Posters” (on view through January 7, 2018). Drawn entirely from the Driehaus collection, the show features posters from France’s famed Belle Époque, with emphasis on Mucha, Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The exhibition is one of several events that prove the staying power of the best Belle Époque posters. On January 26, Swann Galleries of New York auctioned the largest private collection of Mucha works ever to come to market, including pieces that have never been auctioned before. In February, Skira published Alphonse Mucha, a new book by Mucha Foundation curator Tomoko Sato. And on February 4, the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., opens “Toulouse-Lautrec Illustrates the Belle Époque,” an exhibition that will continue through April 30.

The “L’Affichomania” posters appear among the Gilded Age fittings of the grand home that hosts the Driehaus, but they were not designed for interiors. They were meant to enliven the grey 19th-century streets of Paris and catch the eyes of the masses who walked past them. “Until the 1870s, most of the posters put up in the city were mostly text,” says Jeannine Falino, curator of the Driehaus exhibition. “When Chéret began working in lithography, he saw the potential for use in large posters. In so doing, he was able to create very bright images on the streets of Paris.” Bright colors were not merely pretty, but strategic. “They [poster designers] knew their work was ephemeral,” Falino says. “What was up one day could be covered the next day. They had to jump out.”

Chéret earned credit as the father of modern poster design, and he was incredibly popular in his day and long after. His images of joyful women rendered in bold primary colors were famous enough to gain their own name—Chérettes—and Chéret fans held costume parties where they would dress as their favorite poster characters. But leading dealers and auctioneers agree that Chéret’s market has faded in the last few years. There’s no single obvious reason why, and the state of affairs seems more baffling when you consider that his preferred theme, beautiful young women having the time of their lives, is usually a bulletproof artistic subject. Maybe his style is not Art Nouveau enough. Maybe there’s too much Chéret out there—he made at least 1,000 different poster designs.

Fortunately, this market lull does not hold true for Chéret’s most sought-after posters. “The images he did that will stand out and maintain a fairly high price level are the Folies Bergère poster of Loïe Fuller and the Palais de Glace series,” says Mark Weinbaum, a Manhattan-based poster dealer. “They seem to resonate with a lot of people, where a lot of others he designed seem to have fallen on hard times in terms of price level.”

Eugène Grasset did far fewer posters than Chéret, and his style is more Arts & Crafts than Art Nouveau—his women look like sisters of the women in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s paintings. This makes his 1897 Dix Estampes Décoratives series of prints that much more odd and compelling. The Driehaus show includes two original watercolors from the series of 10: Anxieté and Coquetterie. Grasset’s stated intention for the Estampes was to explore the “character of women with emblematic flowers,” but his choice of subject matter ventured into bizarre and shocking territory. La Vitrioleuse depicts a woman holding a pot of liquid and glaring at the viewer. The pot probably holds acid, but the look of pure hatred on her face is enough to burn anyone to the bone without tossing toxic chemicals. Swann Galleries’ house record for Grasset belongs to a La Vitrioleuse that fetched $13,500 in 2005.

If Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen’s Le Chat Noir isn’t the best-known poster image from the Belle Époque, it must be a close second. “Every schoolchild has seen it,” says Nicholas D. Lowry, president of Swann Galleries. “It’s like Mickey Mouse.” Le Chat Noir tackles a theme beloved of Toulouse-Lautrec—Parisian nightlife—but it includes a winking reference to a different poster-designing contemporary of Steinlen’s, Alphonse Mucha. Steinlen ringed his black cat’s head with an elaborate Mucha-style halo.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is in a class by himself. “We would know about Toulouse-Lautrec if he never did a great poster. You can’t say that about the others,” says Jack Rennert, president of Poster Auctions International and Posters Please, a gallery, both in Manhattan. It’s a good thing that Toulouse-Lautrec did choose to create posters, because his first try, Moulin Rouge: La Goulue, of 1891, launched his reputation. “He was little-known as an artist until his first poster,” says Renée Maurer, associate curator at the Phillips. “It had scale, and it had a modernity to it.”

Ask a Belle Époque poster expert to talk about the merits of Moulin Rouge: La Goulue and they will happily oblige, each with their own genuine appreciation of Toulouse-Lautrec’s achievement. “It was just something different,” says Maurer. “People were stopped in their tracks, enchanted by the image. People talked about it.” Lowry comments, “Toulouse-Lautrec couldn’t give a crap about the critics. He was not looking for validation from the art community. That’s one thing that makes it so appealing.” Rennert adds, “For Toulouse-Lautrec, it was his first attempt at lithography. That he succeeded so brilliantly at a medium that he never practiced before is a minor miracle. He gets the swirl of the can-can. You really feel you’re there, that you’re part of the silhouettes in the background. You really feel you’re watching this.”

The Phillips Collection’s Toulouse-Lautrec exhibition allows viewers to see how he shaped his famous Moulin Rouge: La Goulue image by showing it with a unique black and white trial proof. The Phillips also displays a complete, three-sheet version of the poster, which often lost its top sheet because dealers in 1890s France found it tedious to wrangle an image that measured more than six feet long and almost four feet wide in full. “It’s very, very hard to find an original three-sheet Moulin Rouge,” says Rennert. “If you gave me one million dollars today, I’m not sure I could find it for you.” Lowry has handled only one Moulin Rouge, but it was a three-sheet. Swann sold it in December 2008, during the depths of the worldwide financial meltdown, for $300,000, a house record.

While there was a time in the 20th century when Mucha was out of favor, he leaped back into pop culture with the psychedelic designs of the 1960s and has never left. “It’s such an appealing style. People are attracted to it,” says Lowry of Mucha. “Very few people go, ‘Ew, that turns me off.’”

Mucha’s poster debut was as dramatic as a superhero’s origin story. In December 1894, Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress of the time, happened to call on the printing firm where he worked, and asked for a poster to promote her new play, Gismonda. Mucha put his Christmas plans aside and produced a stunning design that thrilled Bernhardt and cemented an artist-muse relationship that endured for years.

Gismonda displays many of the details that characterize Mucha: the Byzantine mosaic details at the top, the halo around Bernhardt’s head, and the singular focus on a beautiful woman. The extremely vertical composition made it extra-novel to Parisian passersby. But Rennert points out that while Gismonda is elaborate, it’s not as heavily detailed as his later poster designs. Bernhardt’s form is sandwiched by large expanses that Mucha leaves empty. “In almost all his other artworks, every inch of the paper is filled with something,” he says. “Because he was in a hurry, he didn’t fill it in.”

Swann’s Mucha-heavy sale contained iconic posters that every Mucha collector has to have, such as Zodiac/La Plume from 1896 and Princenza Hyacinta from 1911, both estimated at $15,000–20,000. Its rarities include Krinogen, a 1928 poster that is among the last he ever made (estimated at $2,000–3,000), and a set of advertising images he created in 1907 for Savon Mucha, an American soap that carried his name (estimated at $3,000–4,000). Both made their auction debuts at the Swann sale. Another poster, Bleuze Hadancourt Parfeumeur, printed circa 1899 (estimated at $15,000–20,000), has only come to auction four times. “Serious collectors cannot wait for this to come up,” Lowry says of the scarcer pieces. “This might be their only chance.”

Lowry’s advice applies to great original Belle Époque posters in general, because the chances to own them are decreasing. “I used to go to Europe every month. Now I go six times a year,” Rennert says. “In the old days—the 1960s, ’70s, and ‘80s—I’d come back with 15 or 20 posters. These days, if I come back with two or three, it’s an achievement.”

—

By Sheila Gibson Stoodley