Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Latter-Day Luminist

While his fellow Washington. D.C. abstractionists cultivated fields of color, Leon Berkowitz found a way to make light emanate from the canvas.

Leon Berkowitz, Merlin #2, 1984, oil on canvas, 72 x 90 in. Credit: © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, COURTESY OF HOLLIS TAGGART

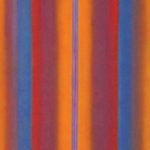

- Leon Berkowitz, Oblique, 1975, oil on canvas, 91 x 35 in. Credit: © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, COURTESY OF HOLLIS TAGGART

- Leon Berkowitz, Untitled, 1963, oil on canvas, 48 x 59 ¾ in. Credit: © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, COURTESY OF HOLLIS TAGGART

- Leon Berkowitz, Merlin #2, 1984, oil on canvas, 72 x 90 in. Credit: © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, COURTESY OF HOLLIS TAGGART

- Leon Berkowitz, Untitled, circa 1960s, oil on canvas, 72 x 48 in. Credit: © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, COURTESY OF HOLLIS TAGGART

- Leon Berkowitz, Golda, 1979, oil on canvas, 100 x 82 in. Credit: Private collection, © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, Courtesy David Richard Gallery

- Leon Berkowitz, Untitled #28, 1975, oil on canvas, 92 x 59 in. Credit: Private collection, © ESTATE OF LEON BERKOWITZ, Courtesy David Richard Gallery

Between 1956 and 1964, the painter Leon Berkowitz and his wife, the poet Ida Fox, traveled throughout Europe. They spent two and a half years in Wales and made trips to London, Paris, Italy, Greece, and Jerusalem. For the painter, who had been a fixture of the Washington, D.C., arts community since the early 1940s, the trip served as a major turning point in his practice.

Berkowitz said of this period, “Living and working as I did during those years in Europe in the open air under expanding skies, light itself became an ultimate goal. I became concerned with the dissolution of matter, the fragmentation of light, the conversion of ‘matter into spirit.’ I wanted to look into color, not at color.” If one were to wonder, what does transcendence look like, Berkowitz’s newfound approach might be an appropriate answer.

He took as inspiration Monet and the American Luminists. He began to think of himself as a “latter-day Luminist,” pivoting away from post-painterly abstraction and the “so-called color school people” who occupied the second wave of Abstract Expressionism.

In the catalogue for “Leon Berkowitz: Big Bend Series 1976,” a 1977 exhibition at the Phillips Collection, the pioneering video artist Douglas Davis wrote, “Leon Berkowitz is often compared and related to Morris Louis, Barnett Newman, and Willem de Kooning—artists whom he knew and admired. But there is a concentration on the experience of seeing (in light) in Berkowitz that reminds me of something Malevich said, thirty years before the appearance of the New York (or Washington) School. He said that the object of painting in the new age is to come alive—to be a living presence. In these works, Berkowitz has found his way to a sentient, sensate center. There is nothing static about what we see. It is beyond form. In the sense of a wall-image in place, the New Berkowitz is beyond painting.” To Davis’s point, Berkowitz wrote in his artist’s statement in the same catalogue, “I want to find the real dimension in which color invokes life.”

In his “mature paintings,” as they are often called, he traded the de Kooning-influenced action paintings of his pre-sojourn work for bars of luminous color and, eventually, soft, unbroken gradations of warm and cool hues. These tones were like the ones that emanate from a neon sign and bounce onto a nearby wall or sidewalk. The ones that feverish Instagrammers race to capture during “Manhattanhenge”—when the setting sun’s smoldering pinks, oranges, and purples align perfectly with New York City’s east-west grid. The ones that Renoir used to portray juicy peaches and apples. The ones that Turner lavished on horizons, rendering sea and sky indeterminate. The ones susceptible to change. Berkowitz took these hues and zoomed into them, as if his paintings were a live feed from a camera that was flying through color and light at a set speed.

Berkowitz was born in Philadelphia in 1911 to Hasidic immigrants from Hungary. He pulled up the rear of a large family, the second youngest of eight. It was in the public schools he attended that his artistic talents were first discovered and nurtured. In the 1940s, poetically, he would become an art teacher in a public school in Washington, D.C.

In the late 1930s, Berkowitz studied art and education on a scholarship to the University of Pennsylvania. It was during this period that he met Fox, who was also a Philadelphia native. They married sometime between 1935 and 1937.

In the summer of 1941, Berkowitz studied at the Arts Student League in New York City under the painter and printmaker Harry Sternberg. The following year, he earned his Bachelors of Fine Arts from the University of Pennsylvania. Shortly after his graduation, he took the Civil Service exam and moved to Washington, D.C., which led to a brief stint in the Department of Justice. But he quickly left this post to teach and then quickly left teaching to serve in the U.S. Army during World War II.

From 1943 through 1945, Berkowitz was stationed at Camp Lee in Virginia, where he worked with psychiatric patients as an art therapist. In an interview conducted in 1979 by the Smithsonian Institute’s Archives of American Art for its oral history project, Berkowitz described how his service dovetailed with his work, noting that his captain, a psychiatrist, wanted an artist to work with psychologists in developing art as a “projective technique.” There, Berkowitz learned psychological methodology like Gestalt and Rorschach. He recalled that “it was hand in glove with the attitudes of the Abstract Expressionists that came from Jung and Freud.” Berkowitz “cold-shouldered” Surrealism, which he saw as a “false mirror of this culture.” Interpreting Rorschach, Berkowitz gathered that symbols weren’t reflections of inner experience, as the Surrealists asserted. “What I learned from the Rorschach was that it wasn’t the symbols that people saw, it was the abstract qualities that they saw, that were diagnostic, you know, a couple of colors, a concern with edges or the hole….all of these things supported the development of my own aesthetic.”

After the war, Berkowitz resumed his position as an art teacher at Eastern High School and Western High School, but he also began a new endeavor. Along with Fox and Helmut Kern, he founded the Washington Workshop Center in 1945. The organization was designed to forge community among D.C.’s fine and performing artists. It became a breeding ground for artists like Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Howard Mehring, Thomas Downing and Gene Davis, who were to be leading figures of the Washington Color School.

In 1953, the Washington Workshop Center held a Willem de Kooning retrospective. Berkowitz forged a connection with Willem and Elaine de Kooning, as well as other figures of the New York vanguard, such as Franz Kline, Clement Greenberg, and the dealer Sidney Janis. These relationships nurtured cross-pollination between the D.C. and New York schools for years to come. In a tribute to Berkowitz after his death in 1987, Sir Lawrence Gowing, former deputy director of the Tate Gallery, London, recalled Kline and Elaine de Kooning insisting, some 30 years earlier, that he call on Berkowitz after they heard he was taking a trip from New York to D.C. “They spoke as if this was more compulsory than any chamber of government or museum of masterpieces,” wrote Gowing. “Here was someone who held with a peculiar strength and constancy to the faith that was animating the whole community of the arts along the eastern seaboard at the moment.”

In 1954, coming off his first solo exhibition at the Watkins Gallery at American University the year before, Berkowitz was featured in Barnett Aden Gallery’s “Abstractions: New York and Washington Artists” alongside Louis, Davis, Theodoros Stamos, and Irene Rice Pereira. That same year, he took a sabbatical from teaching and went with Ida to work for a period in Palma de Mallorca, Spain. “I think there is where I really found myself,” said Berkowitz in the interview with the Smithsonian….there in Spain, I discovered my own isolation.” He recalls feeling “equipped” with his formal education and his contact with artists from Washington and New York and figures like Louis and de Kooning. “So I’d absorbed a great deal. The great question in my mind was whether I had found my own voice. In Spain I came to realize that I had.”

Berkowitz tells of his struggle to find the right studio in which to paint in Spain. Eventually, he found a place on a hill and began painting en plein air. “I set my canvas up against a wall that must have been up there in the time of the Moors. And I was surrounded by just the sky, the sea below it, just endless space. And that’s where I felt comfortable. And I’ve been living in that space ever since.” He created the appropriately titled series, In-spaces of Land, Sea, and Sky, during that trip.

In 1956, The Washington Workshop closed due to lack of funding. The shuttering of the Workshop, however, allowed for Berkowitz’s long trip abroad and the dramatic evolution of his work. Of the Workshop, Gowing wrote, “Looking back one can see how much Leon’s contribution to that second generation, the Washington Color Painters as they were soon called, meant to them and perhaps something of how much it cost him …Now that we know the whole story, we can imagine that he was more aware of what the new doctrine of ‘Color as Content’ could mean, should mean, to a painter like him, more aware than most painters ever are of the vast distance that he had still to travel in order to realize his potential.”

During almost a decade abroad—and nearly a decade of painting en plein air—the vastness of nature had a major impact on Berkowitz. He abandoned action painting and the notion of his personal gesture as a work’s only source of vibrancy. “I wanted to surrender my action to the forces of nature that underlay the facts,” he wrote. “I wanted to find authority outside myself—to paint not only out of myself but out of what was beyond my own body…Action painting seemed too constrained.”

When Berkowitz returned from his travels to the United States in the mid-’60s, he had to parlay his experiences of working in nature into a city practice; it was essential that he not feel constrained again. For a brief period in 1966, he created a group of white paintings, then black and white works. By the end of the year, however, he embarked on the Cathedrals series. In these works he “essentialized” the vertical, painting vertical bands of glowing color that seem to surge off the canvas. “I try to explore it in all its possibilities, the vertical as a cause and result of the color, the shape of the canvas a cause and result of its ascent and inner verticality,” he said.

In Cathedrals, the bands of color are painted on either side of a thin, cake-sliver-like white triangle. This slender wedge, wrote James F. Pilgrim, the curator of “Recent Paintings By Leon Berkowitz”, a 1969 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art and Berkowitz’s first solo museum show (that year, Berkowitz also joined the faculty of the Corcoran School of Art), acts as a symbolic light source. Pilgrim wrote, “Light seems to move laterally from this core, creating changes in color intensity,” but he added parenthetically that “the changes actually result from light reflecting through various densities of pigment.” Berkowitz’s real light source was the canvas itself.

Pilgrim also explains rather eloquently how Berkowitz and the Washington Color Painters, despite their geographical and social proximity, diverged. He wrote of how the Washington painters deployed acrylic resin paints to stain their canvases’ fibers, rendering the canvas itself as a color area. “The color area expands or contracts in relation to other color areas and to the raw canvas, yet it remains essentially flat and unmodulated, with light inactive within it.” Berkowitz, on the other hand, used transparent coats of oil paint on a primed canvas with visible grain. “Light is reflected from the white ground through the transparent pigments creating a brilliant and luminous effect and making the color appear to float between the canvas and the viewer.”

In Berkowitz’s work, there is no spraying or seeping of pigment—and later, hardly any use of shape. Instead the artist developed a method in the late 1960s in which he used large brushes to sweep on a mixture of 10 percent oil paint and 90 percent turpentine. He allowed each layer to dry thoroughly—sometimes using rags or blow dryers—before applying another. He usually applied some 30 to 40 edgeless layers. In the 1970s Berkowitz said, “I have continued to develop this method to a point where I can distribute the fragments of pigment both in extension and depth, resulting in an additive mixture of colored light. The color is therefore seen in space and changes with the solar spectrum as day moves into night.” This creates what he calls a “dynamic form”—something that doesn’t exist in Color School pictures.

Hollis Taggart’s October 2019 exhibition “Thresholds of Perceptibility: The Color Field Paintings of Leon Berkowitz” put on view a dozen large-scale canvases—some nearly nine feet—from the artist’s high period in the 1970s and ’80s. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Jason Rosenfeld writes that the results of Berkowitz’s technique “are certainly Color Field pictures as art history understands that wing of Abstract Expressionism.” But unlike Rothko’s “hovering parallelograms of color clouds,” Berkowitz’s transitions are “seamless between hues.” “And while they seek to bodily envelop the viewer,” he writes, “they do so through a resistance to depth and resolution and a gentle expansion of tones beyond the four sides of the support, unlike the edged monochromatics in Newman’s work.”

In the early ’70s, while living briefly in the SoHo neighborhood of New York City, Berkowitz developed Duality and Untities, two series that announced the establishment of a new style that focused on the graduation of glowing, seamless tone. The Hollis Taggart show featured several examples from his Unities series. Unities No. 12 (1971), features thin slices of green on the top and bottom rendered in landscape format, while its center is dominated by orange blushing bright red and back again. In Unities #31 (1973), the sides, which go from green to blue, are in portrait format, while a pink horizon hugs the bottom edge, creeping into a large wash of purple; Berkowitz called this central field a “single enveloping space.”

Among the other paintings in the show was The Pool II, a 1976 work that Berkowitz said was inspired by the experience of looking down deeply into a body of water. Big Bend No. II (Double Violet), a circa-1976 painting, is part of a series that commanded a solo exhibition at the Phillips Collection in 1977 (it traveled to the Chicago Arts Club, as well). Berkowitz created the series in response to Big Bend, a national park in Texas that is one of the country’s least visited. Of the park Berkowitz said that “it has the appearance of the way the world might have looked on the day of creation.” While there, the artist was reading the Kabbalah and contemplating the idea of “life emanating from darkness,” a concept he tried to emulate in the Big Bend series by rendering light emerging from dark. But the blue in Big Bend No. II (Double Violet) was inspired by his experience of the Blue Grotto off Capri, Italy, in the 1950s.

The pieces in the exhibition from the turn of the 1980s show Berkowitz employing an even lighter hand. Tantric I (1981), which seems almost to evoke shape, brings to mind the abstract Tantric paintings from Rajasthan, India. In Tantric Hinduism, these geometric abstractions were painted and then meditated upon as a method to make a divinity such as Shiva or Tara appear. In works like Transition (1979), dispersal rather than apparition seems to be central. The painter’s layers are so gossamer-like they seem to lift and dissipate into the air.

——

By Sarah E. Fensom