Subscribe to Our Newsletter

The Medium is the Magic

A show at LACMA puts the fantastical aspects of photography on display.

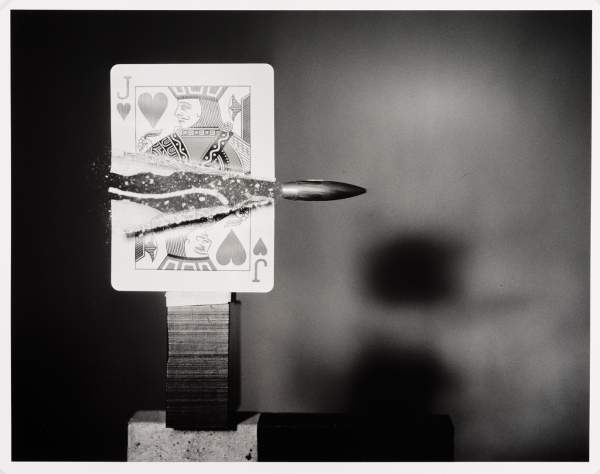

Harold Edgerton, Bullet through Jack of Hearts 1960, printed later, gelatin silver print.

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

- Portrait of 3 Unidentified Men, circa 1850, daguerreotype (1/6 plate) with 4-bracket preserver in leather case.

- Eugène Atget, Eclipse, 1911, printed 1956, silver (gold-toned).

- Lucas Samaras, Photo Transformation 8/19/76, 1976, internal dye diffusion print, manipulated;

- Harold Edgerton, Bullet through Jack of Hearts 1960, printed later, gelatin silver print.

In his 1987 book Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, Ioan P. Couliano discusses society’s interaction with technological development: “Magic and science,” he writes, “represent needs of the imagination, and the transition from a society dominated by magic to a predominately scientific society is explicable primarily by a change in the imaginary.” Couliano’s point could guide a reading of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, though it was written 20 years later. Márquez’s novel, arguably the best-known example of magical realism, describes the Buendía family’s foundation of the fictional Colombian town of Macondo. Various extraordinary occurrences befall the family and the town, while simultaneously, new technologies, such as the automobile, cinema, and the daguerreotype are slowly introduced, disrupting Macondo’s highly spiritual and somewhat fantastical way of life. The daguerreotype camera is met with confusion, if not mistrust—it’s easier for the family to comprehend their own belief system than a new-fangled machine that captures human likenesses. (Once the technology is embraced, however, one family member sets out to capture the image of God.)

Historically, the members of the Buendía family are not photography’s only reluctant sitters. A machine that could automatically turn a moment or experience into a tangible object seems like magic, until, as Couliano suggests, the imagination accepts it as a scientific reality and not a fantastical illusion, or something entirely more sinister. However, photography’s history as an artistic medium is punctuated by illusion. Photographers are able to create pictures that seem at once to be reality and fantasy. “The Magic Medium,” a current show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (until February 7), puts 19 works from the museum’s permanent collection on view. Spanning 150 years, the exhibition explores how photographers have used process, composition, and the decisive moment to conjure spells and perform tricks.

Dhyandra Lawson, curatorial administrator in the Wallis-Annenberg Photography Department at LACMA and the curator of “The Magic Medium,” says that magical realism was an entry point for the show and that she reread One Hundred Years of Solitude in preparation. Lawson cites Untitled (hallway), a 2008 coupler print by Los Angeles-based artist Matt Lipps as an example of a “mystical moment.” Part of Lipps’ 2008 “Home” series, Untitled (hallway) depicts a puff of smoke in the artist’s childhood home. In this series, Lipps affixed cut-outs of Ansel Adams’ photographs to cardboard backgrounds and propped up them up on a table in front of multi-tonal images of his former home, taking a photograph of the standing collage. The result is a combination of the familiar and normal with the unknown and spectacular.

Similarly, William Eggleston, whose photograph Untitled [Building with strange cloud] (circa 1974) is in the show, has an uncanny ability to turn ordinary aspects of life into alluring images. “It’s about finding magic in the ordinary,” says Lawson. “Looking at the roof in this photograph is a valuable endeavor.” A photograph by Eugène Atget shows revelers crowding together on a city street to see something extraordinary—an eclipse. The photography, appropriately titled Eclipse, was taken by the French photographer in 1911, with this silver print printed in 1956.

Harold Edgerton’s Bullet through Jack of Hearts (1960, printed later) features a magician’s prop (is this your card?), but showcases a photographer’s trick. Edgerton captured the bullet sailing through the air, just after it punctured the card, by using ultra-fast stroboscopic lights. Whereas Nic Nicosia’s gelatin silver print Love + Lust #5 (1990) pulls off another form of trickery: the two lovers seen caught in a passionate kiss are hired actors. Says Lawson, “This print in particular is my nod to the cinema.”

This exhibition marks the first time that examples from LACMA’s daguerreotype collection will be on public display. Portrait of 3 Unidentified Men (circa 1850), a daguerreotype plate secured in a four-bracket preserver and leather case, shows three men posing closely together, while Untitled (circa 1850), a daguerreotype with a scallop brass mat, shows a woman regally sitting for her portrait. Daguerreotypes, which were exposed in the dark and developed with the vapor of mercury onto a sheet of silver-coated copper, are reminiscent of the purest crossroads between magic and science: alchemy.

—

By Sarah E. Fensom