Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Pious Fraud

Art Forgery: Lothar Malskat was a master at forging restorations, old-master and modern paintings

In a bombed-out church in wartime Germany, Lothar Malskat crossed the line that separates art restoration from forgery.

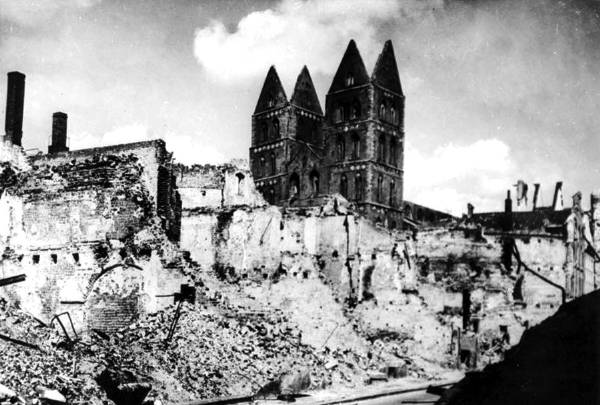

In the early hours of Palm Sunday, March 29, 1942, the Hanseatic city of Lübeck burst into flames. The conflagration was no accident; it was the consequence of a strategic decision the previous month in London. Because British air raids on German factories were missing the mark—seldom striking within five miles of their target—Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided instead to wage war on the “morale of the enemy civil population” by carpet-bombing whole cities. Mainly built of dry, old wood and essentially undefended, ancient Lübeck was prime real estate for the Allies’ first airborne fireworks display.

Two hundred and thirty-four planes dropped nearly 300 tons of incendiary bombs, burning thousands of homes as well as the merchant’s quarter, the town hall and several historic churches renowned throughout Europe for their Gothic architecture. The surprise attack spooked even Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda, who confided in his diary that such raids had the potential to break the people’s will. The National Socialist People’s Welfare] handed out oranges and apples, and the Luftwaffe retaliated with the so-called Baedeker Blitz, vowing to obliterate every town with a three-star rating in Baedeker’s Guide to Great Britain.

Yet the Lübeck people were less impressed with fresh fruit—let alone cultural vengeance in Exeter and Bath—than with an unexpected revelation inside their own 13th-century Marienkirche. Hot enough to melt the church bells, the Palm Sunday fire peeled five centuries of whitewash off the walls, exposing enormous Gothic frescoes painted when the building was erected. Dubbed “the miracle of Marienkirche,” the discovery was sheltered under improvised roofing until the war ended and structural repairs could begin.

By the summer of 1948, the church was fully enclosed again, and a generous sum of 88,000 marks was apportioned for the celebrated restorer Dietrich Fey to conserve the murals. Even from the ground, some 25 yards below the sooty apostles, people could see that the frescoes’ condition was delicate. Climbing the scaffolding, Fey’s assistant, Lothar Malskat, confirmed their gravest concerns. Scarcely a shadow of the original paint remained, as he later recalled, “and even that turned to dust when I blew on it.” Preserving the miracle of Marienkirche would require a miracle-worker.

Three years later, on the Lutheran church’s 700th anniversary, West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer stood in the nave amid ministers and dignitaries. “Das ist erhebend, meine Herren!” he declared—“This is uplifting!”—and he lifted up his arms to rows of 10-foot-tall Gothic saints. Radiant in red, green and ocher, the Marienkirche miracle became a sort of solace for a whole downcast nation. As in all miracles, however, there was an element of the inexplicable. Though nobody cared to examine the recent past, a comparison between the murals and photographs taken in 1942 showed that some of the saints had moved and that Mary Magdalene had lost her shoes.

Dietrich Fey did not so much earn his reputation as inherit it. His father, Ernst Fey, was a respected art historian and restorer in Berlin whose prestige was bolstered in the early ‘30s by the rise of the Nazi party and his talent for ingratiating himself with such self-styled connoisseurs as Luftwaffe commander-in-chief Hermann Göring. Accompanied by his son, Professor Fey restored paintings in churches throughout Silesia. He imparted to Dietrich his historical expertise, and the young man shared his aptitude for courting patrons. But Dietrich Fey lacked his father’s touch with a brush. Securing important ecclesiastical commissions in the medieval Upper Silesian towns of Oppeln and Neisse, Fey and Son were in urgent need of an assistant by 1936, when a 24-year-old house painter named Lothar Malskat came asking for work.

The haggard appearance that Malskat had acquired by living on park benches belied his prestigious background. In his native East Prussia, he’d studied art at the Kunstakademie Königsberg, where his professors praised him for his “extraordinary, almost uncanny versatility.” Filled with optimism he moved to Berlin, seeking fame but finding anonymity. Professor Fey put Malskat to work whitewashing his home. In return for the labor, Fey lent him books on ecclesiastical art. And gradually, in the old churches of Oppeln and Neisse, the professor taught Malskat his craft.

Then, in 1937, Fey and Son brought Malskat to the ancient town of Schleswig, to assist them in a restoration of profound historical significance. The city’s cathedral, St. Petri-Dom, originated in the 12th century as a Romanesque basilica and gradually grew in physical stature as the province of Schleswig-Holstein increased in worldly power. St. Petri-Dom was the seat of bishops for half a millennium and the burial place of King Frederick I of Denmark, whose tomb was carved in the 1550s by the renowned Flemish sculptor Cornelis Floris de Vriendt.

Each stage in the cathedral’s development is preserved in distinctive artwork. The earliest images, on the walls of the cloisters, or schwahl, were first painted around 1300. With the passage of centuries, though, the biblical scenes were gradually degraded by dampness, to such an extent that in 1888 church authorities hired the painter August Olbers to mend the damage.

His repairs, praised at the turn of the century, were deemed a calamity by the 1930s because Olbers had restored by repainting. He could scarcely be blamed. By the standards of his time, restoration meant renovation, a perfectly reasonable, if slightly naïve notion: The purpose was to let people see again what once had been. In the 1930s, a rather different though equally naïve principle was in place: that the restoration must in no way impinge upon the original work. Writing about the conservation of ecclesiastic painting in 1926, the Cologne art historian Otto H. Förster articulated the new orthodoxy. “There must be no element of addition, completion or other conjectured reconstitution of any supposed original state,” he wrote. Olbers was guilty of all three affronts.

Down in the schwahl, Malskat and the Feys set to work, attempting to reclaim history by scraping away the paint with which Olbers had tried to recapture the past. But subtracting what their predecessor had done—whether on account of Olbers’ pigments or the Feys’ incompetence—left almost none of the original paint. A nearly 700-year-old national treasure had vanished, and Ernst Fey was legally responsible for the disappearance.

Most likely Fey was the one to think of a fix. Unquestionably Malskat was the one who achieved it. Over the next several months, the erstwhile housepainter whitewashed the brick, discoloring his lime with pigment to give the walls an ancient tint. Onto this fresh surface he painted freehand his own version of the murals. Necessarily these were based on Olbers’ 19th-century restorations, reverse engineered to approximate the early medieval originals by reference to period examples in the professor’s catalogues. Drawing his figures in earth tones, Malskat took up the spare 14th-century style with preternatural ease and an utter lack of inhibition. He rendered his father as a prophet, and gave Christ the face of an old classmate. For the Virgin Mary, he had to look farther afield to find a suitable model, choosing a woman already widely worshipped—the Austrian movie star Hansi Knoteck. (Apparently 20th century art forgers had a thing for actresses. For the Dutch forger Han van Meegeren, it was Greta Garbo.) Ernst Fey then aged the contour drawings using a procedure he called zurückpatinieren—a fancy word for rubbing them with a brick.

The critical response to the Schleswig restoration was ecstatic. Especially influential was the endorsement of Alfred Stange, an eminent art historian at the University of Bonn who had previously instructed the Nazi elite at the Reichsführerschule and remained a close confidant of Alfred Rosenberg, the chief party ideologue. Praising Fey for orchestrating a restoration “as restrained as it was careful,” Stange lauded the reconditioned murals as “the last, deepest, final word in German art.” And so it came to passin 1940, when Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler ordered that Stange’s illustrated book, Der Schleswiger Dom und seine Wandmalereien, be distributed to all German schools.

Within the Nazi context, the schwahl’s educational value was significant. According to Stange, the paintings represented “an excellent demonstration of the ties, permanent because they spring from nationality, which bind Schleswig to the Saxonian-Westphalian area and its art.” In other words, the murals could be used to promote Third Reich nationalism. Perhaps more important, the figures conformed to appropriate racial stereotypes, confirming the purity of the German bloodline. As Malskat later put it in an interview with the Hamburger Abendblatt, “I had to paint the apostles as long-headed Vikings because one did not want Eastern round-heads.”

The greatest zeal, though, was reserved for the so-called Schleswiger Truthähnbilder, eight paintings of turkeys embellishing a depiction of the Massacre of the Innocents. The turkeys were first pointed out by an independent historian named Freerk Haye Schirrmann-Hamkens in a 1938 article for a local newspaper. Schirrmann-Hamkens brought up the turkeys because their appearance in a mural allegedly painted circa 1300 was surprising: Turkeys are New World birds believed to have first been introduced to Europe by the Spaniards in the 1550s. Of course Schirrmann-Hamkens couldn’t question the authenticity of paintings that were under Himmler’s protection. Instead, he used the paintings to question history. By his reckoning, the Schleswiger Truthähnbilder showed that Vikings had discovered America—and brought back gobblers to the Fatherland—centuries before Christopher Columbus was conceived.

Schirrmann-Hamkens’ theory was bound to be popular. Already the Nazis were championing a 1925 tome by a Danish librarian arguing that the German explorer Didrik Pining had reached America in 1473. A 13th-century Nordic conquest of America that brought turkeys to Schleswig was even better, serving even more firmly to establish the supremacy of the German race (not to mention their Viking pedigree). “The portrayals are based on a high degree of personal observation,” Stange wrote of the turkeys in his 1940 essay. (“They are not, as so often, borrowed from reference books,” he added, lest anybody think that the Vikings had merely raided a library.) Turkeys in early medieval Germany became a part of the Nazi orthodoxy, and were put to work on behalf of the Third Reich propaganda machine. “Aryan seafarers went to American long before Columbus did,” a guidebook to St. Petri-Dom advised tourists. “Incidentally, Columbus is the descendant of Spanish Jews from Barcelona.”

Dissent came from an unexpected source. Nearly 80 years old when Malskat’s restoration was complete, August Olbers emerged from retirement to assert that the Schleswiger Truthähnbilder weren’t proof of circumnavigation by Vikings because he himself had painted them in the late 1880s. Olbers explained that he had not intended to fool anyone. Unable to discern what had originally filled the wall space beneath the Massacre of the Innocents and loath to leave it empty, he’d come up with a motif of foxes and turkeys to symbolize the guile and gluttony of the murderous King Herod.

Malskat had seen Olbers’ anachronistic turkeys and, untutored in ornithology, assumed that they belonged to the original medieval composition. He had so liked the look of them that he doubled their number to eight. The zeitgeist of the Third Reich covered his mistake. In fact, even Olbers was unable to discredit the Fey and Son restoration and debunk the Viking legend. His recollections were disparaged as senile delusions, his memory challenged by experts who dutifully quashed their qualms about Fey’s restoration. They endorsed the St. Petri-Dom forgeries as a sort of pious fraud—a splinter of the Holy Cross or a Shroud of Turin for the National Socialist state religion. Arcane art history could be debated, but the murals had become politically sacrosanct, and professing faith in their authenticity was tantamount to believing in the Fatherland.

Half a decade later, the Fatherland was kaputt. Captured by Allied forces, Himmler committed suicide. Rosenberg was hanged at Nuremberg. Stange was dismissed from his university post. The Vikings retired to the fjords.

Malskat emerged from the war unemployed and broke. Discharged from the Wehrmacht, he attempted to survive as an artist, painting erotic pinups that he peddled on the streets of Hamburg. By the summer of 1945, his circumstances were dire. He sought out his old employer.

Fey seems to have been the only man in Germany unaffected by the war. Though his father had not survived, and the restoration trade was moribund, he still lived in much the same style as when Malskat first encountered him in 1936, wearing fine suits and smoking fancy cigarettes. He gave Malskat a room in his servants’ quarters and put him back to work.

The new business was different, but familiar enough. Instead of faking restorations, Malskat forged old-master and modern paintings. Fey supplied him with yards of canvas and a list of desirable names. Rembrandt. Watteau. Munch. Corot. Chagall. Picasso. To keep up with orders from collectors in Frankfurt and Munich, Malskat had to work fast. “Sometimes I copied an old painting in a day,” he later recalled. “It took me an hour to do a Picasso. But what I liked best was to do new paintings in the style of the French Impressionists.” Among the 70-odd artists he imitated over the next several years in some 600 oils and watercolors were Renoir, Degas, van Gogh, Gauguin and Utrillo.

As might be expected given the scale and speed of production, the quality was uneven. One Frankfurt dealer made the mistake of showing a Malskat to Chagall, who was notoriously unable to detect counterfeits of his own work. For once Chagall had no trouble perceiving the fraud, and destroyed the forgery with his own hands. The dealer just shrugged off the loss and never again sought Chagall’s opinion.

There were plenty of buyers, enticed by economic conditions. With the fall of the Third Reich, the German economy was ruined, and most transactions shifted to the black market. Wary of hyperinflation, people used cigarettes as currency and sought to protect their savings by purchasing commodities such as art. The majority of new collectors were inexperienced, and since many of the most valuable paintings had been looted from foreign museums or seized from Jewish collectors during the Holocaust, asking questions about provenance was verboten. Leading people to believe they were beneficiaries of others’ misfortune, Fey transferred attention from the artifact to the transaction. He made people complicit in his transgression. Because the purchase was illicit, they trusted that the artwork was authentic.

And for a brief period, it made no difference. Since most everyone accepted the paintings based on their attribution, they traded freely, a colorful surrogate for money. Those who were artistically savvy cynically suspended disbelief. The pious fraud was no longer political; it had become economic.

The West German Currency Reform of 1948 effectively ended the black market. Supported by the Marshall Plan, the new Deutschmark superseded dubious old paintings—and even American cigarettes—as the medium of exchange. The Deutschmark was introduced in June. One month later, quick-witted Fey came to Malskat with a new proposition. In the heat of war, an old church had been engulfed in flames, and the fire had revealed an unknown medieval mural. People deemed it a miracle, and were calling for a conservator. On the strength of his success in Schleswig, Fey secured the contract to restore Marienkirche in Lübeck.

The selection was controversial. In a sealed report filed with the provincial Culture Ministry, Schleswig-Holstein state curator Peter Hirschfeld wrote that “the restoration of defective medieval mural paintings is, in the last analysis, a question of trust. Dietrich Fey will not guarantee that he has never done any overpainting in an unguarded moment. I therefore declare that I disassociate myself from the working methods of the restorer Dietrich Fey. I decline all further responsibility.”

However the church authorities were determined to hire Fey and to have his restoration bring the attention to Marienkirche that it had to St. Petri-Dom 80 miles away. “Paint out the church beautifully,” advised the Lübeck bishop, Johannes Pautke. Further encouragement to enhance the murals was given by the church superintendent, and most emphatically the chief architect, Bruno Fendrich, who exhorted the restorers to “preserve the religious impression,” reminding them that “we want no museum.” According to Malskat, Fendrich’s favorite refrain was “Immer Farbe druff!” (Lay on more paint!)

Malskat laid on more paint than even Fendrich could have hoped. Scaffolding was erected to bar entry into the nave, and signs were posted warning of danger overhead. Fey instructed the masons to start hammering whenever anyone approached, warning Malskat and his assistant, Theo Dietrich-Dirschau, to conceal work in progress behind wooden panels. With those precautions in place, the two men scrubbed the walls and reprimed the brick. On the fresh surface, Malskat repainted apostles and saints that had previously been only faint and incomplete. He worked quickly with bold lines and bright colors, covering in days the square footage that would have taken a more conventional conservator months.

The speed with which he painted put the project ahead of schedule. By the summer of 1950, he’d recreated all the 14th-century murals in the nave. A year remained before the 700th-anniversary festivities, so Fey had scaffolding erected in the choir and proposed that Malskat discover an additional cycle of murals.

Since the walls were blank, Malskat had no visual constraints. Within the limitations of the era he was faking, he was free to create. To an extent, he worked from books, in particular Morton H. Bernath’s classic 1916 survey of painting in the Middle Ages, Die Malerei des Mittelalters. His murals also borrowed liberally from earlier periods, for instance a 9th-century depiction of a Coptic saint in Berlin’s Kaiser Friedrich Museum. Nor did he forget his father or Hansi Knoteck, both of whom once again were models in absentia, as was Grigori Rasputin, who he cast as a bearded king. He painted in local laborers as monks. He portrayed himself as a patriarch. Within months the walls of the choir were resplendent with art. Twenty-one Gothic figures stood 10 feet in height, embellished with friezes of animals and flowers: The Marienkirche miracle had a surprise post-War sequel.

Amidst all this secret activity, only one expert seems to have managed to ascend the 70-foot scaffold uninvited, a doctoral student by the name of Johanna Kolbe. Though she didn’t witness Malskat at work, she had a unique opportunity to scrutinize the paintings with a magnifying glass rather than binoculars. What she saw appalled her. She informed municipal authorities that the paint was applied “much too thickly” and also noted a few oddities in the nave, such as the disappearance of Mary Magdalene’s sandals. Fey accused her of defamation. She decided that her memory must have been faulty.

That left only acclaim. “Ideas hitherto current as to the original aspect of Gothic brick interiors will have to be revised in light of the merits of the works here recovered,” wrote Lübeck Museum director Hans Arnold Gräbke in a monograph on the murals, Die Wandmalereien der Marienkirche zu Lübeck. Noting stylistic similarities to the frescoes in Schleswig, he dated the choir murals to the 13th century, an assessment echoed by the art historian Hans Jürgen Hansen in a second treatise. “They exhibit a severe style, Byzantine-influenced and still almost Romanesque,” Hansen observed, contrasting them with the 14th-century paintings in the nave, which he found “more animated, softer, entirely Gothic.” Even the dour Peter Hirschfeld came around, calling the murals “the most important and extensive ever disclosed in Germany, in fact one of the finest intact frescoes of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries extant throughout western Europe.”

The 700th anniversary of Marienkirche was celebrated in that spirit. Chancellor Adenauer declared the murals “a valuable treasure and a fabulous discovery of lost masterpieces.” Louis Ferdinand, Prince of Prussia (and grandson of the late Kaiser) offered his royal congratulations. Reproductions of the murals were printed on two million postage stamps, issued in 10- and 20-pfennig denominations. Articles were published in periodicals around the world, including Time magazine, which pronounced the paintings “a major artistic find,” informing readers that “the interior of the Marienkirche looks more as its original decorators intended than it has for 500 years.”

Das ist erhebend! Over the following months, 100,000 people visited the church, buffeting Lübeck’s faltering economy with revenue from tourism. The murals of Marienkirche were miraculous indeed, seemingly able to provide for the city’s every need.

The only person who didn’t find the miracle of Marienkirche uplifting was Lothar Malskat. While restoring the church, he often quarreled with Fey, who paid him a mere 110 marks a week out of the 88,000 Deutschmark budget. When Malskat protested that he was doing all the work, Fey reminded him that he was just an anonymous assistant; the Hanseatic City of Lübeck had hired Dietrich Fey, the acclaimed conservator of St. Petri-Dom, to restore Marienkirche.

More than he minded the low pay, Malskat resented the anonymity. As he worked in the nave, and especially in the choir, he grew increasingly attached to the paintings, convinced that he was not their restorer—nor even their forger—but their full-fledged creator. He inconspicuously marked some of the figures with his initials. At one point he wrote, “All Paintings in this Church are by Lothar Malskat.” Fey promptly had his words whitewashed.

The 700th-anniversary celebrations left no doubt as to Malskat’s position. He watched Fey take full credit for the murals and receive all the accolades. Fey was publicly honored by Adenauer, granted an additional 150,000 marks in restoration money and nominated for a prestigious university professorship in Bonn, while Malskat was left to drink bottled beer with the masons.

Malskat’s resentment festered for eight months, while he worked for Fey on smaller restoration projects in the Lübeck Rathaus. Repeatedly he confided to Dietrich-Dirschau his intention to get even with his imperious boss and gain the recognition he craved. Each time he lost courage. Then, on May 9, 1952, he abruptly entered the police station and announced that the Marienkirche murals were counterfeit. He had faked the medieval paintings on Fey’s orders, he said, and was confessing because “that crook Fey” had treated him unfairly.

Nobody believed him. The cops labeled him a crackpot, a local newspaper proclaimed that “this is the lamentable case of a painter gone crazy,” and the good people of Lübeck proposed to have him committed. They refused to scrutinize their miracle, even after Malskat submitted photographs taken with his Leica documenting his creative progress from whitewashed walls to finished frescoes.

Malskat appealed to the national media. The unknown painter’s sensational claims garnered him interviews on radio and television. He pointed out the figures based on Rasputin and Knoteck, and Die Welt printed photos of murals next to their purported sources, including the Coptic saint in the Kaiser Friedrich. To any unprejudiced observer, the resemblance was unmistakable. Lest openmindedness prevail, the city of Lübeck issued an official statement. “Rumors and accusations against the renowned art expert Doctor Fey are of no consequence and purely malicious gossip.” The walls of Marienkirche had been reclaimed from oblivion; now they needed to be protected against defamation.

Unable to get himself and Fey arrested for their fraudulent restoration of Marienkirche, Malskat returned to the Lübeck police station in August, confessing to their pre-war forgery in the Schleswig schwahl. If anything, that admission only further damaged his credibility: The crackpot artist was now also deemed a megalomaniac. Fendrich and his fellow Marienkirche officials went on record with a signed decree: “Any charges at present being leveled at the restorer Dietrich Fey are as yet insufficient to rouse our misgivings. The work of preservation will therefore continue under the restorer Dietrich Fey.”

Malskat hired an attorney by the name of Willi Flottrong. He told the lawyer not only about the bogus restoration work but also about the phony Picassos and Rembrandts. Handing over a folder of evidence, he instructed Flottrong to file charges against Fey and himself, legally compelling the police to act. Flottrong submitted the portfolio to the prosecutor on October 7.

Two days later, Fey was detained while police searched his house.

They found 7 paintings and 21 drawings counterfeited by Malskat, including forgeries of Matisse, Degas, Chagall and Beckmann. No longer could the conservator or his restorations be protected. A commission of experts was dispatched to examine the murals of Marienkirche. On October 20 they published a report. “The twenty-one figures in the choir are not Gothic, but painted freehand by Malskat,” the committee wrote. “The painting described as old by the restorer, Fey, does not lie on the medieval layer [of mortar] but on a post-medieval layer, and cannot, if for this reason alone, be considered original.” The report also confirmed that the murals in the nave had been repainted.

This time, the Lübeck bishop himself spoke up. Conceding that the murals were fake, Pautke asserted that “if the restorer Dietrich Fey has fraudulently succeeded in getting his work recognized as faithful restoration, this was possible only because of an extremely cunning deception which misled not only the church administration, as proprietor, but also curators and art experts.”

However nothing rankles quite like the fraudulently pious. In the face of such monumental betrayal of the public trust, the courts were unwilling to accept as a foregone conclusion the innocence of anyone. Over the following 10 months, the prosecutor amassed hundreds of hours of testimony. Embarrassing questions led the church superintendent to request early retirement and another high official to depart for East Germany. In the several-hundred-page indictment, Bruno Fendrich was named co-defendant.

Thus the trial of Malskat and Fey also became a trial of the institutions that had supported them. “The real defendants are not the forgers, but the experts and officials who failed to exercise proper care,” editorialized a local newspaper. “They didn’t mind being deceived. Had Malskat not photographed the empty church walls before he started painting his murals, the evidence would have been suppressed by the very people who employed him. They are as much to blame as the forgers themselves.”

The case was too big for the Lübeck courthouse. In order to accommodate all the people clamoring to watch the trial, proceedings were held in the Saal des Atlantiks, a dancehall popular for its swinging music, popularly known as Stimmung und Schwung. The bar was draped to lend sobriety to the hearing, and the number of spectators seated on the dance floor was limited to 400, though several hundred more paid the Atlantiks janitor 20 pfennigs an hour for a chair in the garden, where they could hear the testimony on loudspeakers.

The trial began on August 10, 1954. Asked why he had confessed, Malskat told the tribunal and the people of Lübeck—as well as the nearly 50 reporters in the press box—that “everybody raved about my beautiful murals, yet Fey got all the credit. Nobody even knew my name.” From that moment on, he was the center of attention.

He presented himself as the unacknowledged master he considered himself to be, speaking of the consummate ease with which he had decorated Marienkirche. (“I love to do 13th-century painting,” he quipped “Nothing to it.”) At the same time (and somewhat inconsistently), he disparaged the connoisseurs who had praised his forgeries. “One art critic raved about the ‘prophet with the magic eyes,’” he said. “It was modeled on my father. Another gushed about the ‘spiritual beauty of the splendid figure of Mary, so far removed from our present day image of womanhood.’ For that painting I used a photograph of Hansi Knoteck.”

Of course with this new knowledge, people could no longer see these figures as the critics had in 1951, believing them to be ancient. From the vantage of the trial, the forgery of Marienkirche was unfathomable. “At a time when X-ray apparatus, quartz lamps and the most modern technical equipment seem to exclude the possibility of large-scale art forgeries,” asked the prosecutor, “how could a second-rate painter have fooled the nation’s leading experts?”

“People like to be fooled today,” responded Malskat. “We just gave them what they wanted.”

What people did not enjoy was knowing that they’d been tricked. On January 26, 1955, after more than five months of testimony, the court reached a verdict. “Although the ascertainable material damage done may not have been excessive, it seriously endangered the restoration of Marienkirche as a whole,” asserted the presiding judge. “The dishonest behavior of those engaged upon it undermined confidence in the proper execution of all the reinstatement work.” In other words, the offense was not fundamentally a crime of property damage. The infringement was psychological: Robbery of faith, theft of a miracle . After Fendrich and Dietrich-Dirschau had been sternly chastised, Fey was sentenced to 20 months in prison and Malskat to 18.

His reputation ruined, Fey never restored his career in conservation. Malskat fled to Sweden, where he attempted to capitalize on his celebrity and prove his artistic genius by soliciting commissions. He decorated Stockholm’s Tre Kroner Restaurant in 14th-century Gothic style and recycled his Schleswig turkeys in ersatz murals for the Royal Tennis Court. Extradited to Germany in late 1956, he served his jail term and then faded into obscurity, eking out a living as a self-styled expressionist for his remaining 32 years.

However the most punishing treatment was reserved for Marienkirche itself. With the verdict, Peter Hirschfeld turned with a vengeance on the murals he’d been led to admire several years before, stating that “the forgeries should first be plastered over so as to obtain a clear surface free from all theoretical preconception and thus enable careful plans to be laid for an ideal solution of the problem by substituting true works of art for forgery, honesty for insincerity, with consequent obliteration of the stain upon morality. It should be considered the duty of any truly Christian community to carry out this task.”

In the choir, Hirschfeld had his way. Malskat’s transgression was covered up by workers, and by and large forgotten. In the nave, the opposite viewpoint prevailed. “The nave forgeries were deliberately left as they were,” noted the restorer Sepp Schüller, conservator of the Suermondt-Museum in Aachen, writing about the scandal in his 1959 book Forgers, Dealers, Experts. “They constituted a sort of warning to all concerned with art, either as amateurs or professionals.”

The contradictory responses reflect our emotional ambivalence toward a betrayal of trust: whether to obliterate or to commemorate the offense. Yet whichever decision is made, the sting of injury will pass, and people will recover their belief. According to the Lübeck entry in Rough Guide: Germany—a Baedeker for the 21st century—”Gothic frescoes of Christ and saints add colour to otherwise plain walls [of Marienkirche]; the pastel images only resurfaced when a fire caused by the 1942 air raid licked away the coat of whitewash.” Malskat is not mentioned, nor is his moral stain apparent in the church. For a new generation of tourists, the murals are again miraculous.

Adapted from In Praise of the Fake, forthcoming from Oxford University Press.

—

Article By Jonathon Keats