Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Rejecting the Standard

In the early 20th-century, American modernists challenged conventional art norms by painting emotional and design-filled images of the times.

By Barbara A. MacAdam

At the “Dawn of a New Age: Early 20th-Century American Modernism” opened May 7 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This illuminating show of modernist American works created between 1900 and 1930, often looks fresh to our eyes in 2022, much in the way we find ourselves captivated and appreciative of 1960s and ’70s conceptualism. The Whitney has just chosen the right moment to pull these many selections out of storage and gather them together with newly acquired works of the period, many by lesser-known modernists. The show, on view through January 1, 2023, enables us not only to see these images but also to contextualize them in unexpected ways. In this light-filled Renzo Piano–designed contemporary-modernist structure, we can view the Hudson River to the west giving substance to our sense of art and time in motion, while, off to the east, there is the city itself, as it was and sort-of-still is—that is, the solid appearance of real life. To understand this expansive gathering requires us to take a whirlwind tour of the show and assess the gestalt.

Stuart Davis (1892-1964), Egg Beater No. 1, 1927. Oil on linen, 29 3⁄16 x 36 3⁄16 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.169. © 2022 Estate of Stuart Davis / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From this vantage point, we can get a panoramic portrait of America in transition, with its enthusiasm for the new propelled by advancing technology and at the same time, acknowledging respect for the old; its optimism about the future and its potential to accommodate change; and its eagerness to find a place for itself in an uncertain country full of idiosyncrasies and the creative energy of a range of immigrants.

Here is a kind of snapshot of a less-than-coherent time. It touches on the complexity of American culture—at once sophisticated and provincial—still European-tinged and yet very American. The works embody the variousness of the artists’ backgrounds reflecting their economic situations, their politics, religious propensities, spiritualism, and their moral and emotional turmoil and financial insecurity.

Modernism is, by definition, a reaction against the past—several pasts, in the Whitney’s case, including the gritty realism of The Ashcan painters and the stuffiness of the academicians—and this is embodied, particularly in the many styles of abstraction in evidence, involving the taking apart of reality, and reexamining and reconnecting of its parts in new modalities. Cubism, both synthetic and analytic, is a natural contender for this kind of speculation, allowing for an intense look at the inner workings of art— how that art engages reality, and decouples from it and the mind as it deals with the body in perception.

Veteran curator Barbara Haskell has assembled around 60 works by some 45 artists who were at once celebrating and resisting social and technological change, representing a link with our own uncomfortable moment. Most interesting, in this regard, is that the Whitney itself initially favored more traditional art in its collecting and subordinated new and nonrepresentational works in its purview.

Patrick Henry Bruce (1881-1936), Painting, ca. 1921-2. Oil on canvas, 35 x 45 3⁄4 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of an anonymous donor 54.20

It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that the museum began to acquire art from the between-the-wars period of 1900 to 1930. Most of the pieces in this show are from the Whitney’s own collection, and consequently, constitute a comfortable and fitting extension of its holdings, which include important and exceptional works by the expressionistic painter Marsden Hartley, the playful Polish American sculptor Elie Nadelman; the visionary artist Charles E. Burchfield; and the moody colorist and former architect Oscar Bluemner, who suffered anti-German sentiment, couldn’t sell his work and ultimately killed himself.

These are representative examples of the variety and singularity of the works on view by a predominantly white male group; although there are striking exceptions, such as the African American Rhode Island and Paris trained portrait painter-sculptor Nancy Prophet, whose Africa-evoking wood portrait bust sweetly punctuates the woodcuts in the first gallery by Harlem artist and illustrator Aaron Douglas and cut-paper pieces by the Hawaiian Isami Doi.

But there are also new—to me—discoveries, including the likes of the intricate decorative cubist Jay Van Everen, with his riotously active Abstract Landscape (circa 1924), and John Covert, whose sculpturesque cubism in his painting Resurrection (1916) seemingly links him with Arthur Dove, whose paintings were considered to be among the first abstractions in America. Covert’s forms warrant close reading in his work’s originality—a large sculptural tongue shape holds the foreground, overlapping an apparent stone pyramid, actually composed of fabric. Altogether, we delve into a forest of cubist forms with a quirky red dot winking at Corot as it holds our eye.

Joseph Stella (1877-1946), Der Rosenkavalier, 1913-4. Oil on linen, 24 1⁄8 x 30 1⁄8 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of George F. Of 52.39

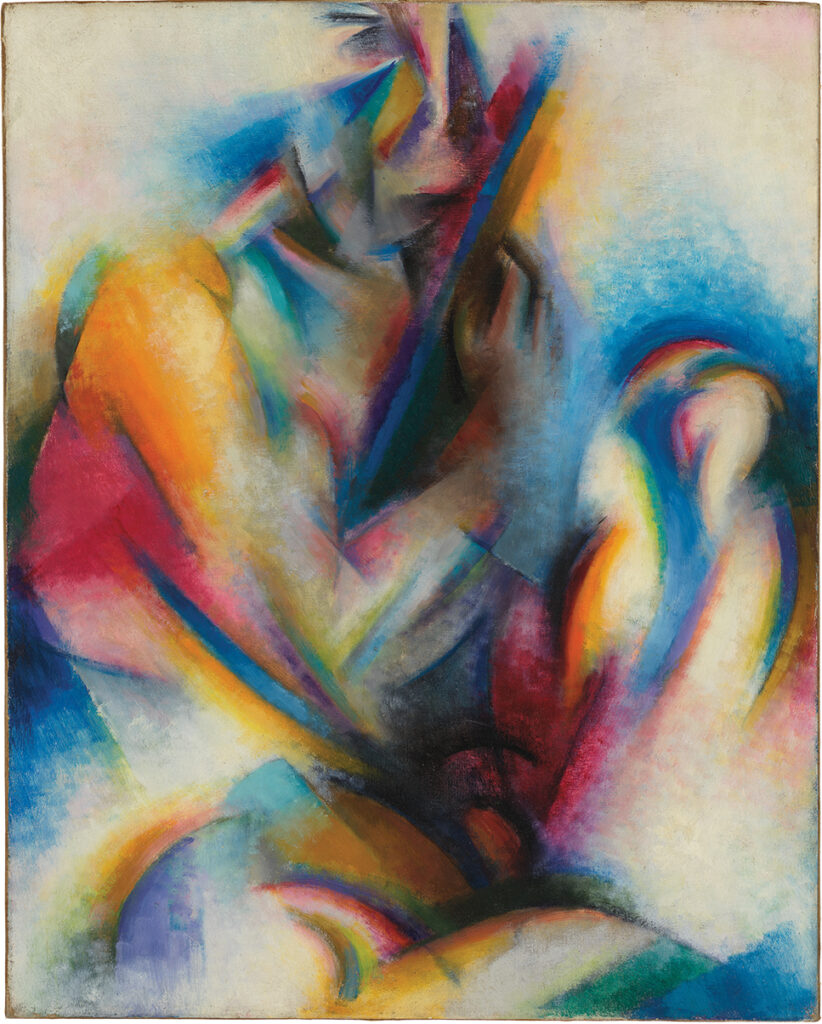

Color is its own subject in the painting of Stanton Macdonald-Wright, one of two creators of synchronism, a movement dedicated to pure abstraction. He explained in 1916, “I strive to divest my art of all anecdote and illustrations and to purify it so that the emotions of the spectator can become entirely ‘aesthetic,’ as in listening to music.” Comedian-musician Steve Martin told MoMA Magazine that he liked the artist’s works because they seemed “lonely.” And “pure color and the juxtapositions of different areas of color could create all of the composition that is needed.”

One particular surprise is Untitled (1928), a red-chalk-on-paper line drawing by the formidable Ukrainian-born American artist Louise Nevelson, best known for her monumental wood sculptures. But this drawing, depicting three female nudes—perhaps graces—is an elegant rendering, at once strong and delicate, subtly built atop an image of a face.

In fact, the women in the show cover the gamut in origin, style and originality, ranging from Marguerite Zorach, noted for her Fauvist-spiritual paintings, such as the dreamlike gouache Landscape with Figures (1916), collaging delicately limned trees and human figures; Georgia O’Keeffe, of course, with her Music, Pink and Blue No 2 (1918), embodying her many concerns, from rhythm to landscape to sexuality; the German-born Transcendentalist painter of the desert Agnes Pelton, with her flat organic renderings; photographer Imogen Cunningham with a seductive blossom, and then the sophisticated American saloniste Florine Stettheimer, who irresistibly documented New York cultural life.

As women were treated so dismissively during the period, excluded from professional arts organizations, it’s important to note the inventive ways they managed to channel their talents. We can see, for example, graphic design and storytelling in the painting of the British-Jamaican artist Pamela Colman Smith, whose illustrations show the influence of Art Nouveau, most notably in her children’s’ book designs and her tarot cards, which, by necessity, became a source of income for her.

Jay Van Everen (1875-1947), Abstract Landscape, ca. 1924. Oil on canvas, 25 5⁄8 x 25 5⁄8 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry M. Reed 68.32.

Standard-bearer Stuart Davis sets the stage here with a witty Pop-like painting Egg Beater No. 1 (1927), emerging out of Cubism. To create this image, resembling a picture of an assemblage, Davis affixed an eggbeater, an electric fan and a rubber glove to a table in his studio. In so doing, he composed a composite cubistic abstraction—a house with a roofline, a grassy green pathway and undesignated shapes all collaged together.

The far less known painter Patrick Henry Bruce, a descendant of the statesman Patrick Henry, also produced such very flat (and forthright) paintings using geometric forms and ordinary objects, like a top hat poised at different angles in vivid colors. He’d taken his cues from the Parisian avant-garde, especially from Matisse, and Sonia and Robert Delaunay. His version of synthetic Cubism was marked by a space-defining bar to the left of the picture. Ironically Bruce, with his bright, clear, apparently confident and critically well-received paintings went on to suffer depression and ultimately commit suicide.

From the near-Surrealist works of Ben Benn, who was born in the Ukraine, to the China-born Yun Gee, a colorist and chronicler of street life in America, to the German-born Bluemner, whose Old Canal Point (1914) captures the artist’s preoccupation with emotions and color, we learn how so many artists of the time never managed to achieve critical acceptance and financial stability and consequently succumbed to despair.

Rounding up the exhibition is an exemplary room featuring a highly spiritual and elusive oil pastel on paper by Joseph Stella from 1919–20 depicting an abstract woman’s figure, absent face, in sheer blue with her pubis defined by a decorative floral bouquet. This elegant fertility figure, symbolically titled Nativity, hangs near Stella’s more frenzied almost futuristic operatic oil painting with embedded figures–Der Rosenkavalier from 1913-14—that calls to mind the work of the Portuguese painter Vieira da Silva.

Stanton Macdonald-Wright (1890-1973), Oriental – Synchromy in Blue, 1916. Oil on canvas, 30 1⁄8 x 24 1⁄8 in.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of the Kiley Family in memory of Erhard Weyhe 2021.155.

Europe is always calling out from the sidelines, as can be poignantly and dramatically detected in the firm assertive hand of Hartley. His strong outlining and heavy gesture owe much to the Blaue Reiter artists and the military pageantry that excited him in Germany. He succinctly tells his story in paint. The Maine-born artist moved to Paris, where he became attracted to Cubism and Fauvism and the spiritualism of Kandinsky. After World War I, a soldier he’d fallen in love with was killed and Hartley adopted for his still lifes the imagery he associated with his lost love.

We can contrast this very concrete approach to the forceful expressionistic gestures of Max Weber, the Polish-born Jewish American painter who even made excursions into writing cubist poetry, demonstrating how to build compound visual structures with words.

Finally, taking a different poetic route is E. E. Cummings, with his jazzy Noise Numbner 13 (1925), a dynamic presentation of loud trumpets, which is almost an exercise in synesthesia—we can hear the look of sound. It’s a brilliant note to end the show on.

We are viewing here not only the ascendancy of abstraction as a movement, but also its variability and shiftiness—how it is capable of absorbing and expressing styles and stories and emotional realities.

Dominating the show as we round out our tour is the realization of the innovative spirit and ingenuity that pervaded America.

Embedded in all these largely abstract conglomerations are history, storytelling, religion, mysticism and the excruciating personal trials of the artists. In these relatively intimate gallery spaces, the artworks, more modest in size than we are accustomed to viewing today and in the variousness of their approaches, speak to one another and to us in carefully modulated tones.