Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Robert Mapplethorpe: Another Perfect Moment

A two-museum retrospective in Los Angeles highlights Robert Mapplethorpe’s enduring oeuvre and legacy.

Robert Mappletorpe, Orchid 1987

Featured Images: (Click to Enlarge)

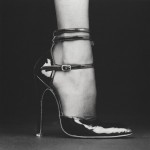

- Robert Mappletorpe, Shoe (Melody), 1987

- Robert Mappletorpe

- Robert Mappletorpe, Self Portrait

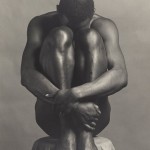

- Robert Mappletorpe, Ajitto (1981)

- Robert Mappletorpe, Orchid 1987

In the majority of the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s work, sex is casually or rather blatantly present. In his black and white floral close-ups—such as Calla Lily (1988)—which are reminiscent of the studio portraits of Irving Penn or Richard Avedon, flowers have the supple sexuality of bodies. Photographs that depict nude bodies—such as Lisa Lyon (1981)—which harkens back to the Neo-Classicism of 19th-century Pictorialist portraits, take on the delicacy and unselfconscious beauty of flowers.

Yet others, such as the artist’s series “X Portfolio” on the underground BDSM scene in late 1960s and ’70s New York, or those depicting homoeroticism or simply the relationships between gay men, such as Larry and Bobby Kissing (1979), depict sexuality explicitly. The artist even depicted himself as a sexual fetish object, as in Self-Portrait (1980), where he is seen sitting in front of the camera, smoking and leather-clad, wearing the hairstyle of 1950s teenage rebellion: the pompadour. Photographs from the “X Portfolio,” which were on view in the 1988 exhibition “The Perfect Moment” at the Contemporary Art Center in Cincinnati, led to the indictment of the museum and its director, Dennis Barrie, for obscenity by the city of Cincinnati (the jury ultimately found Barrie and the CAC not guilty), and the eventual cancellation of the show at its next planned stop, the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Additionally, Mapplethorpe, who died of AIDS in 1990, is often associated, not only with the AIDS crisis but also with the culture wars of the 1980s and with gay life in general.

Yet regardless of content or cultural associations, Mapplethorpe strove to express the totality of his vision as an artist—to direct and capture images of what he found visually appealing: the slick sheen of leather, the glistening smoothness of musculature, the satin-like texture of flower petals. Beauty, with an emphasis on self-directed perfection, was Mapplethorpe’s ideal—an aesthetic that seemed to reach an apex in the art world of 1980s New York.

In Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids (2010), the author and musician recalls a day in the ’60s when she and Mapplethorpe, her boyfriend at the time, found sketches by Touko “Tom of Finland” Laaksonen among some used paperback in Times Square. The sketches, which showcased leather-clad, physically fit young men atop motorcycles, left a lasting impression on Mapplethorpe. Though he studied art at Pratt and was exposed to photography early on by his father, an amateur photographer, Mapplethorpe was not enamored of the camera or the photographic process. Born in Queens, N.Y., and coming of age in the New York of the ’60s and ’70s, Mapplethorpe was drawn to Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg—not only to the former for his fame and persona or the latter for his glamour-meets-grunge lifestyle, but to both for their use of the photograph in works that were not necessarily about photography. In his early work, such as Leatherman #1 (1970), Mapplethorpe used found images from gay porn magazines and scrap materials to create collages. The artist and filmmaker Sandy Daley lent Mapplethorpe a Polaroid camera in 1970. This was a pivotal moment in Mapplethorpe’s art-making process. With the camera, he effectively stepped into the role of auteur, conceiving of images and producing them to his standards of perfection rather than finding them and piecing them together.

“Robert Mapplethorpe: The Perfect Medium,” a major retrospective co-organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, is now on view at both museums through July 31. “Mapplethorpe’s motive for art-making was not about medium, but about his idea of perfection,” says Britt Salvesen, curator and head of the Wallis Annenberg Photography Department at LACMA. “He said that in another era, he could have been a sculptor. However, our title addresses photography being the perfect medium for him.”

LACMA and the J. Paul Getty Trust made a joint acquisition of art and archival materials from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation in 2011. Along with a joint gift from the foundation that same year, the acquisition privileges both institutions with the ability to stage the most comprehensive survey of Mapplethorpe’s work to date. Says Getty director Timothy Potts, “The rich photographic holdings in the Getty Museum and LACMA, together with the artist’s archive housed at the Getty Research Institute, make Los Angeles an essential destination for anyone with serious interest in the late 20th-century photography scene in New York.”

Further contextualizing Mapplethorpe’s work, “The Thrill of the Chase: The Wagstaff Collection of Photographs,” a concurrent exhibition at the Getty (also until July 31), puts on view the collection of Sam Wagstaff—Mapplethorpe’s partner and an accomplished collector and curator. Wagstaff’s photography collection, which was acquired by the Getty in 1984, has served as one of the backbones of the Department of Photographs at the museum. Boasting classic works of photography such as an albumen silver print of Gustave Le Gray’s The Great Wave (circa 1857), an albumen silver print of Mrs. Herbert Duckworth (1867) by Julia Margaret Cameron, and a gelatin silver print of Philippe Halsman’s Dali Atomicus (1948), Wagstaff’s collection is a veritable history of photography.

Mapplethorpe, who did not print his own images but felt strongly about the photographic object, most certainly reveled in the quality of Wagstaff’s vintage prints. While Mapplethorope “wasn’t always forthcoming,” as Salvesen puts it, with his photographic influences, Wagstaff’s cache of prints by Man Ray, Edward Weston, and Roger Fenton were in his purview. In particular, the Boston-based 19th-century Pictorialist photographer and publisher F. Holland Day (whose photographs Wagstaff did collect) comes to mind when looking at Mapplethorpe’s portraits throughout the ’80s. A paragon of dreamy Neo-Classical portraits and the dandy lifestyle, Day has multiple examples of the African American male nude (or partial nude) in his oeuvre.

Like’s those of Day, Mapplethorpe’s photographs, such as Thomas (1987), Ajitto (1981), Ken Moody (1983), and Derrick Cross (1983), which all appear in the Getty’s iteration of “The Perfect Medium,” idealize the black male body as Greek sculptors did the bodies of athletes during the Classical period. Mapplethorpe, who had a fascination with black skin, used three models of different racial backgrounds in his 1985 photograph Ken and Lydia and Tyler (also on view in the Getty show) to evoke the ancient mythological trope of the Three Graces. Shot in black and white, as the lion’s share of Mapplethorpe’s photographs are, the gradation of skin color highlights not only the beauty of the three unique bodies but also the tonality of the image.

Mapplethorpe’s interest in highly developed bodies is well documented. His long-time muse Lisa Lyon, with whom he created 184 portraits over the course of six years, was a female bodybuilder Mapplethorpe met at a party in 1979. Of Lyon, the first woman to win the International Federation of Body Builders female competition, Mapplethorpe is quoted as saying, “I’d never seen anybody that looked like that before. Once she took her clothes off it was like seeing something from another planet.” Mapplethorpe’s work with Lyon culminated in the 1983 photography book Lady, of which multiple images can be seen at LACMA’s iteration of “The Perfect Medium.” Patti Smith, Mapplethorpe’s other female muse and of course his longtime companion, could not be physically more different than Lyon. (Though both women were androgynous in their own way, Lyon was muscular, Smith lanky and soulful.) Portraits of Smith, such as Patti Smith (1979), not only capture the close relationship between the two artists but also chronicle their life in the still-heralded, bygone days of Max’s Kansas City, the Chelsea Hotel, and the gritty, exciting downtown New York scene. In the LACMA show, the two short films Mapplethorpe made are both on view; one, titled Still Moving, stars Smith, the other Lyon.

Smith has had a lot to do with Mapplethorpe’s legacy, especially in recent years. “Patti Smith’s book reopened peoples’ eyes to Mapplethorpe and why he wanted to be an artist,” says Salvesen. “It is an honest portrayal of a young man who believed he had something to say and how he was going to do that.”

Though both museums certainly want to place the quality of Mapplethorpe’s work over content or controversy, the artist’s legacy as a social figure undoubtedly factors into “The Perfect Medium.” “We now have some social distance from the time period from which he was working and making statements about his lifestyle and life,” says Salvesen,” and the situation in our country with gay civil rights is totally different now, but it’s good to look back and recall those different circumstances. For younger people who weren’t around when the culture wars played out in the late ’80s and early ’90s, it’s important to remember that debate about freedom of expression.”

—

By Sarah E. Fensom