Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Roy Lichtenstein Retrospective: National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

In the National Gallery’s huge Lichtenstein retrospective, the iconic Pop images are just the opening frames of the artist’s lifelong comic strip.

By Ted Loos

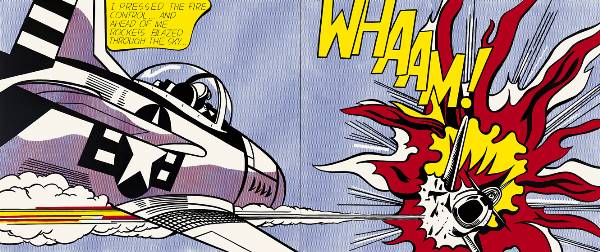

Whaam! Varoom! Ratatat! Torpedo LOS!

Those are the sounds you’re hoping to see, as it were, at a Roy Lichtenstein exhibition, and the very big one that opens this month at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., features those famous comic-book exclamations, bright and bold and eye-grabbing in their painted form, and many more.

Those are the sounds you’re hoping to see, as it were, at a Roy Lichtenstein exhibition, and the very big one that opens this month at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., features those famous comic-book exclamations, bright and bold and eye-grabbing in their painted form, and many more.

The show is the first full-on retrospective of the artist’s work since the one at the Guggenheim in 1993, when Lichtenstein was still alive, and this version (it opened at the Art Institute of Chicago this summer) is packed with 150 works, many of them loans delicately extracted from top collections around the world.

The best-known paintings on view are the famous Pop works of the 1960s, with their fantastic fighter-jet explosions (Whaam!, from 1963) and blondes dramatically emoting on their rotary phones (Oh Jeff, I Love You, Too, But…”, from 1964). In a way, though, those works are the bait to get people inside the exhibition and deepen their understanding of Lichtenstein’s enduring work, which went far beyond the handful of images that made it to T-shirt status.

As James Rondeau, the Art Institute curator who co-organized the show, put it to me, “We want the iconic things, but we also want some new information.” Rondeau and Sheena Wagstaff, late of the Tate Modern and now of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, spent four years meticulously putting the exhibition together, laboring over dollhouse-sized maquettes of the layout of the pictures (if they had added a Barbie, she probably wouldn’t have known how to appreciate such a Dream House, but her blond mane would have fit right in).

Now that it has moved to Washington, the curators there see the retrospective as a chance to re-connect with large numbers of people—an opportunity that their other fine exhibitions of late—of the Ashcan School artist George Bellows and Surrealist Joan Miró—probably can’t quite provide in the same way. “It’s going to be a mass audience, that is for sure,” says Harry Cooper, who coordinated the National Gallery run.

The museum has been beefing up its Lichtenstein holdings, in fact. “We have a great commitment to his work here,” says Cooper. That commitment is largely due to the super-collectors Robert and Jane Meyerhoff, who have given four major Lichtenstein paintings to the museum and have promised a trove of 15 more—a “done, signed deal,” as Cooper says.

Regardless of where the individual pieces come from, as a whole the exhibition demonstrates that Lichtenstein, while never giving up his signature Benday dots and illustrator’s eye for brilliant simplification and reduction of form, ambitiously addressed all of art history in his work. He took on Picasso, Monet haystacks and the greatest abstract sculptures of all time—always with a playful irony that sometimes spilled over into outright jokes. If he had lived longer, surely he would have given us a take on a Jeff Koons puppy, too. His widow, Dorothy Lichtenstein, phrased it this way when I spoke to her about the show: “He loved poking fun at things.”

Dorothy, also by far the biggest lender to the show via his estate and the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, is among those behind the scenes who are thrilled to round out people’s perceptions of Lichtenstein’s work. “I think when people think of Roy’s work they immediately think of cartoons,” she says. “They’re more surprised by the later work.”

His “Imperfect” series of the ’70s and ’80s, with its jagged, irregularly shaped canvases, is a good example. It helped him explode out of the constraints of the traditional picture plane, with its rectangular limits shared by the comic strip frame. Imperfect Sculpture (1995) is essentially a series of triangles assembled in one pointy piece, with colors that directly reference Piet Mondrian’s classic abstractions. But these works are mostly unknown to the general public—ditto his Chinese landscapes.

In a work like Treetops through the Fog (1996), Lichtenstein deploys his Benday talents to the most haunting and delicate effect, managing to evoke rippling water, misty mountains and elusive cloud shapes all with the changing scale of the dots. But unlike Georges Seurat’s pointillism—so famously on display in the Grande Jatte, the Art Institute’s most famous picture, which would have been great in the same room as the Lichtenstein show for a Dot-Off competition—he calls attention to each point instead of trying to make them disappear. As Cooper puts it, the interest comes in “the space between the original works and his reduction of them.” And he reminds us that it’s not just an exercise in cleverness: “They’re beautiful, too.”

The exhibition’s substantial number of drawings and other works on paper also helps set it apart from previous Lichtenstein shows. Drawings don’t generally galvanize museum visitors—somehow they are seen as less juicy and inviting than paintings—but those who knew the artist best see them as the key to his enduring art.

“The drawing really is where you can see the art part,” Dorothy told me. “I know he always felt, if you look at a Judd or a Flavin drawing, you can tell they’re really artists.” What she means is that despite the simplicity of their finished Minimal pieces, they were building forms from the ground up, like engineers.

Lichtenstein wasn’t stealing panels from comic strips wholesale—he was inspired by a huge range of sources, but then he filtered and personalized them. The next step was architectural, constructing complex images with great precision. In Interior with Painting of Reclining Nude (Study), from 1997, we see a paper-on-board attempt to create the initial bones of one the very last paintings he made before he died.

To the end, he is balancing the shapes, cross-hatching and dotting with exquisite sensitivity. The colors are his typical primary hues, but pinks and browns have also crept into the composition. The outline of a reclining woman’s face, that art historical odalisque figure he returned to so often, is far to the right, and she’s looking away from the rest of the picture. Perhaps she’s looking for what’s coming next, the inspiration over the horizon—certainly Lichtenstein always was.

This article originally appeared in Art & Antiques Magazine as “Dot, Dot, Dot.”