Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Street Artist

By Edward M. Gómez

In the Swiss mountains, Hans Krüsi found flowers to sell from his Zürich pushcart—and the inspiration to create a major body of outsider art.

Hans Krusi, Drawing of concentric circles on vellum-like paper

- Hans Krusi, untitled, mixed-media

- Hans Krusi, untitled, mixed-media

- Hans Krusi, Drawing of concentric circles on vellum-like paper

- Hans Krusi, paint-on-board picture, 1984

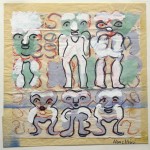

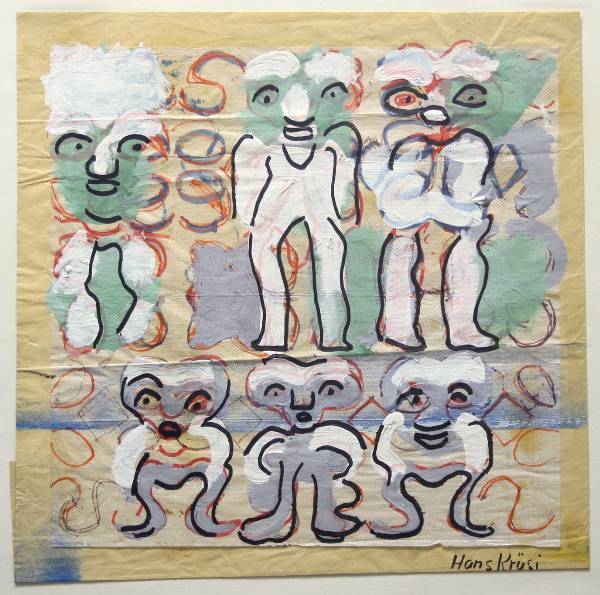

- Hans Krusi, Drawing on restaurants’ paper napkins, felt-tip pen and gouache

Some records note that Hans Krüsi (1920–95) was born in Zürich; most others say he was born in the town of Speicher, in Appenzell Ausserrhoden, a small, German-speaking canton in northeastern Switzerland. He was born to a single mother and was brought up by foster parents and, later, in an orphanage. Krüsi received only an elementary-school education, and his childhood was a hard one, although the art he would later make often refers back to the verdant landscapes of his rural youth with a sense of reverence and nostalgia.Krüsi dreamed of studying to become a gardener, but since he was obliged to work as a farmhand before he could set out on his own, ultimately he went on to acquire gardening skills through various odd jobs, not through formal training.

A gaunt, eccentric loner, Krüsi was poor and moved around frequently. He lived most of his life in or near St. Gallen, one of Switzerland’s larger cities, near the south side of the Bodensee (Lake Constance), the body of water that forms part of the country’s border with southern Germany. After the end of World War II, while still in his 20s, Krüsi began commuting regularly from St. Gallen to Zürich, where he set up a flower-selling stall on the Bahnhofstrasse, one of Europe’s most elegant shopping streets. To acquire his merchandise, Krüsi made forays into alpine valleys, where he would pitch a tent and enjoy a few days of rejuvenating mountain air before heading back to the city to sell his freshly picked bouquets.

In the mid-1970s, Krüsi began making postcard-size drawings and paintings on scraps of paper or cardboard and offering them for sale along with his flowers. Soon he was also making simple line drawings with felt-tip pens on the thin-paper napkins he found in the cafés and inexpensive restaurants where he took his meals. Krüsi took pleasure in the way his inky images and patterns soaked through the absorbent paper of his Serviettenzeichnungen (German for “napkin drawings”), instantly creating variations on an array of motifs—cows, human figures, flowers and abstract, serpentine designs—in a four-quadrant format that emerged when he spread out each folded sheet. “What I make, no one can make [again] after me,” he said in a 1981 interview.

That kind of inimitability is what outsider-art collectors and dealers crave, now more than ever. Today, the seven-decade-old field is facing some big challenges, partly because its turf is being invaded by the contemporary-art field and partly because of the scarcity of the best, new material that afflicts all art fields. Some longtime dealers complain that the outsider marketplace is being diluted by works that either do not properly fit the definition of the genre or are of low quality and overpriced. In this climate, educated eyes are turning to certain artists who are not exactly unknown but whose accomplishments deserve more critical and market attention than they have received to date. One of them is Hans Krüsi.

From the start of his art-making career, Krüsi depicted subjects from the rural settings in which he had grown up—farm animals, cats, birds and vistas of the countryside, with mountains, chalets and forests. He once told an interviewer, “Most of all, I love to paint cows.” He also drew inspiration from the urban environment in which he lived and worked as an adult. Krüsi moved frequently throughout his life, often residing in low-rent, run-down structures or even squatting. In one of his home/studio spaces on the top floor of a nearly empty building, the prolific artist lived with cats and with pigeons that he allowed to fly in through open windows and nest atop stacked-up crates or in the curved arms of ceiling lamps.

In 1980, Felix Buchmann, the director of the now-defunct Galerie Buchmann in St. Gallen, “discovered” Krüsi’s work and offered him a contract to become his art dealer; the struggling street vendor’s first-ever solo exhibition opened at the gallery in January of the following year. In a recollection of that event, which she penned several years later, Berti Ammann, the wife of the Swiss curator and art historian Heinrich Ammann, noted: “There seemed to be no end to the [viewers’] desire to buy.” Krüsi, she recalled, “moved contentedly through the stream of visitors, with a growing sense of self-consciousness.” The Swiss press ran with the story of the humble flower-seller turned cultural figure who, before too long, was proudly handing out business cards that identified himself as a “picture painter.”

After Krüsi’s death in 1995, the Kunstmuseum des Kantons Thurgau, in north-central Switzerland, received as a bequest artworks, personal papers, photographs and notebooks from his estate. The museum, in the village of Warth, in the canton of Thurgau, is housed in a section of a former monastery and had already earned recognition for conducting research about and presenting the work of Swiss self-taught artists.

In a book published to accompany an exhibition of Krüsi’s art that was shown at the museum in 2001, its current director, Markus Landert, then its curator, wrote, “Who then was Hans Krüsi? To this very simple question there is no easy answer.” That is because, Landert suggested, there were at least two Krüsis: There was Krüsi the man, whose life story was one of hardship and eccentricity, and also Krüsi the artist (or the constructed artist-personality), to whose activities and Aussenseiter (“outsider”) status that same biography was inextricably linked. In truth, like many outsider artists, Krüsi’s worldview was deeply informed by the culture and society in which he lived and worked, and because he achieved fame and success as an artist and became a recognized force and presence in the Swiss cultural world of his time, he also achieved a certain kind of contemporary cultural relevance. Like those of any significant artist, his ideas—about his subjects, about art, even about his homeland—mattered to his audience. Those facts led Landert to ask, “As what [exactly] do we want to regard Hans Krüsi?”

The answer may be found in the art-maker’s work itself, for one of the most remarkable aspects of Krüsi’s multifaceted oeuvre is the fact that, in it, viewers can find plenty of evidence showing that the energetic autodidact regarded himself as both a genuine artist and also as someone who was self-consciously playing the public role of an artist from almost as soon as he started making little pictures to sell along with his flowers. For example, among the material from Krüsi’s estate that Landert and his curatorial team have sorted out and archived over the years are thousands of photographs the artist shot throughout his life. Many of them, from his later years, are color Polaroid snapshots showing Krüsi relaxing in the countryside, in his signature artist’s costume of second-hand clothes and a hat decorated with real or plastic flowers; or greeting guests at the openings of his exhibition; or admiring his handiwork in his art-filled home/studio, where he covered every square inch of wall space with his boldly colored works. Often Krüsi is seen in these photos holding or standing near flowers, which were emblematically associated with his personal history.

Using a reel-to-reel recorder and, later, a cassette recorder, Krüsi also made hundreds of audio recordings of ambient sounds, including church bells ringing, cows mooing and birds chirping. All of these items are now stored at the museum in Warth; with them, Krüsi captured and preserved not only some of the sources of his artistic inspiration but also some of the defining aspects of his self-conscious Swiss identity. Landert notes, “Krüsi used his photographs to help construct and document his persona as an artist. Obviously, this identify was very important to him; it is the one he projected publicly.” One representative work in the museum’s collection consists simply of the raised, wooden, orange-painted initials “H.K.,” mounted on a framed backing board, like a minimalist corporate logo.

Partly because the outsider market is always so hungry for new material of high quality from hitherto unknown artists, and partly because Krüsi’s paintings, drawings and sculptures offered such an unusual take on the traditional, local imagery that was a notable part of his subject matter—his psychedelically colored rabbits, chalets and landscapes were not the normal stuff of Swiss folk art—the works of the “Appenzeller outsider,” as the Swiss media dubbed him, sold well, beginning with Buchmann’s 1981 show. At the beginning of Krüsi’s 15-year-long professional career, some of his works fetched from 180 to 500 Swiss francs apiece (about $170 to $470 at today’s exchange rate); at the time of his death, some of his largest works were selling for as much as 28,000 Swiss francs (around $26,385 today). Nowadays, the smallest Krüsi works may be found for less than $1,000; many small to medium-size pieces are priced at less than $10,000.

Sadly, there were times when unscrupulous buyers tried to take advantage of Krüsi. One former, reputable dealer in St. Gallen who knew the artist well, considered him a friend and did a lot toward the end of his life to help him live comfortably, if still very modestly, in the way the artist preferred, recalls: “Some people went to Hans’s studio, got him drunk and bought up works for unfairly low prices while the artist was too tipsy to understand what was going on.” Then there were the times, in the 1980s, when Krüsi’s residences were burglarized, and his artworks stolen. After one break-in, the artist told a newspaper reporter that he supposed the thief or thieves who had robbed him could have been familiar with the art world, a place in which, he noted, “plenty of grubby figures” could always be found.

By contrast, the Swiss businessman Werner Fischer followed Krüsi’s development from his first appearance on Switzerland’s art scene and routinely purchased works from galleries that showed them. Over time, he built up a substantial collection of Krüsi’s creations in diverse media; Fischer and his wife, Anita, befriended the artist and were instrumental in taking care of him right up until the time of his death.

Anita Fischer recalls, “It’s remarkable how capably Hans made his way through and survived in a complex world, for there was definitely something naïf about him even though, at the same time, he was very clever. You wanted to protect and encourage him and what he represented—his talent, vision, honesty and purity.”

Andrew Edlin, whose New York gallery presented Krüsi shows in 2002 and 2004 and continues to handle his work in the U.S. market, notes that in recent years some of his pictures were shown in group exhibitions of selections from the collection of the London-based Museum of Everything (founded by the British collector James Brett) in London and in Torino, Italy. Edlin points out that “the demand from Swiss collectors, especially, for Krüsi’s works, as well as their prices, continue to increase.” As this issue was going to press, an avid Krüsi collector in northern Switzerland discovered a dozen of the artist’s small, text-and-images-filled notebooks in the hands of a more general collector in another part of the country. “I immediately made an offer,” says the specialist collector. “Among dedicated Krüsi fans, this material is as rare and as highly prized as it gets.”

As a man and as an artist, Hans Krusi embodied the sense of independence and originality that have always been essential sources of value in the field of outsider or self-taught art. As for dealers, the most passionate purveyors of this kind of art have always tried to find work with these qualities and bring them to market. In recent years, this spirit has touched a nerve with a growing audience of contemporary-art aficionados who are tired of encountering art products that are habitually filtered through or that merely serve as exercises in tired, too-familiar postmodernist critical theory.

Even with the financial challenges he regularly faced before his professional fortunes changed, the health problems he wrestled with later in life and the occasional mistreatment he suffered from unscrupulous art buyers, Krüsi was nothing if not keenly self-aware. So it was that, with a mixture of pride and gratitude, he once observed that he had been “a nothing” who, most unexpectedly and rewardingly, had become “a something.”